Are you trying to introduce dogs to each other?

In this episode of The Dog Show, I discuss the best way to introduce dogs and how long it takes to do so with Ian Stone.

Ian is the owner and principal trainer of Simpawtico Dog Training. Simpawtico uses intelligent and creative training techniques to help you manage, motivate, and learn about your beloved canine family members.

Ian also has a Master’s degree in teaching from Southern Oregon University and lives with his wife and four dogs in upstate New York.

Find out more about Simpawtico Dog Training here:

Listen

Watch

Read

Will: This episode of “The Dog Show” features Ian Stone. Ian is the owner and principal trainer of Simpawtico Dog Training. Simpawtico uses intelligent and creative training techniques to help you manage, motivate, and learn about your beloved canine family members. Ian also has a master’s degree in teaching from Southern Oregon University, and lives with his wife and four dogs in Upstate New York. In the interview, we discuss the best way to introduce dogs to each other and how long it takes to do so. Ian Stone, welcome back to “The Dog Show” once again.

Ian: Thank you for having me, Will. I appreciate it.

Will: Yeah, I’m really excited to have a chat today about introducing dogs. So I’ve had you on the show before. We’ve spoken about puppy socialization. And on an earlier episode, Episode 20, we did kind of a full rundown on biting and chewing. But today, we’re talking about introducing dogs. So what’s the best way to introduce dogs? It’s a pretty broad question, but go for it.

Ian: Oh boy, man. Well, okay. So in a nutshell, the best way to do it is if the dogs don’t know each other, which obviously they wouldn’t if you’re introducing them, is to do it on neutral territory. You don’t want any weirdness about a dog getting possessive about a yard, or a living room, or a couch, or something like that. So neutral territory for the first meeting is usually pretty good. I know there’s a couple schools of thought, and I’ve done it both ways. One school of thought is that take the dogs on a parallel walk together if they can handle it. That’s usually a good way to just get some good exercise, just get some good endorphins on that, and then have some kind of drive-by interactions before you ready to go for a full interaction.

Now, that depends on the dogs. If you have dogs that are absolutely crazy driven to go to each other, then that doesn’t really work. That makes it really, really difficult to try to do a parallel walk. And this is a situation I went into because I work at the shelter and we do playgroups with the dogs there a lot. And we’re introducing new dogs to each other all the time. And so our activity pen is, kind of, the neutral territory that we use. You really can’t do that parallel walk with a lot of those kinds of dogs because once they see another dog, they’re so starved for social interaction that they’re…I mean, it’s like trying to wrangle a torpedo. So you kinda have to do this little dance. So I’m going to attempt to break down the dance in layman’s terms without getting too technical.

So essentially, you have to understand when dogs are friendly that they approach on an arc, they very rarely make a straight beeline for the other dog. They tend to approach on an arc if they have friendly intentions. Now, some of these dogs that might be meeting might not have the social background to know to do that, they might be unsure, might be slightly reactive, and they may make a beeline, but you should try to have them approach on an arc. So if we’ve got both of these dogs on a leash, you got one savvy handler with one dog, another savvy handling with the other one, and you should circle each other, and just kind of spiral in closer, and closer, and closer so that you’re getting, kind of, oblique or at least perpendicular contact, and then we’re trying to get them to go nose to nose. Nose to nose is kinda, like, the doggie handshake.

The big thing to remember with that is that if you’re doing this on-leash, restraint tends to increase drive. And you don’t want drive with dogs that are meeting each other because then they just collide. You don’t want the dogs to come in with a bunch of drive nose to nose. So as scary as it is, and I tell all of my staff that I’ve trained at the shelter to do this, is that last 18 to 12 inches, you’ve gotta just let the leash go. Don’t drop it, but let the leash go so that it is completely slack when they come in nose to nose. There are tons and tons of dogs in the world that are just absolutely drag racers on the leash and are in drive. And if you were to drop the leash, they would just toddle up to a dog and be like, “Hey man, how’s it going?” So you have to have that first nose to nose with no tension on the leash. And that’s really scary for a lot of people. I mean, you know, my clients in my school, when I tell them that, like, you can just see their body clench up even thinking about it. But it’s really, really necessary.

Now, depending on how that goes, I usually recommend that you give it a one Mississippi or a two Mississippi, and then you peel out, and you start circling each other. So you peel out, you kinda make clover leaves, you get a little bit of distance so they can kinda decompress just a second, and then you spiral in, and you just lather, rinse, repeat until the dogs are savvy enough with each other and comfortable enough with each other that you can maybe even let the leashes go or at least stop it and try again tomorrow.

So some of the other pieces of that, without getting into super technical detail, is re-exposure makes it less interesting. So every time you kinda come in nose to nose and then peel out and come back nose to nose, each one is less intense than the one before. So you can usually ease down. We’ve had a lot of dogs that we’ve introduced to each other in the shelter that I know lots of people would be like, “Oh, that’s it. They can’t. They’ll never be able to play.” But if you do those repeated exposures with a lot of good support and encouragement, you don’t wanna reprimand dogs for doing stupid things because they will blame it on the other dog and then they’ll think meeting dogs gets them in trouble. So you just have to deflect, you have to control the situation, and just keep it simple.

If they get too crazy, peel them out. If you go and loose leash and it’s going really nice, and then somebody starts to do something stupid, a lot of times, you can just deflect and just be like, “Hey, don’t do that.” Deflect them off, and then they’ll circle around and come back, and you’re, kind of, right back where you started. We’ve had dogs at the shelter, I can think of two right now, Neo and Atta [SP], this was a couple of years ago, that they looked like they were gonna kill each other. But I remember that me and my assistant, we were like, “You know what, though, I can see little jewels in here.” And it took us about three days of just constant exposure, exposure, exposure on-leash, and managing, and managing, and managing. And those dogs actually became so close that they got adopted together to the same home. They were inseparable, absolutely inseparable.

So you can overcome a lot with good introductions. But light leash control, not a lot of coercion, no jerking, you don’t wanna reprimand them, but you wanna have, you know, firm guidelines. If somebody is gonna start mounting or getting growly, then you gotta get them out of there and just be like, “Nope, we’re not gonna do that.” So there’s a lot of moving parts to it. But if you follow those, if you just, kind of, either do a parallel walk or you spiral in together on-leash and then peel out after a second, keep re-exposing, you can usually overcome most silliness pretty quickly.

Will: Is there something about the leash? From personal experience, I feel like, for some reason, our dog…and she’s got better and better over time, and we’ve used similar techniques to what you’re talking about. But, like, when she’s on the leash, there’s almost more chance that she’ll, like, introduce, meet a dog, and kinda go a bit crazy, and do the things she shouldn’t do. Whereas, if we’re in the dog park, for example, and she’s off-leash, it’s like she’s just chilled and she just, kind of, just says, “Hey, how are you doing,” to the other dogs.

Ian: Exactly.

Will: Is there something about that environment that makes them, you know, act differently?

Ian: Absolutely. It’s the leash. So a leash, it takes options off of the table. And so a dog knows that they don’t have the freedom to approach or to move away as much as they do in a dog park where they’re completely unfettered and they can manage that interaction completely on their own. And what you described, Will, is super, super, super common where we have dogs that are leash-reactive, but perfectly fine when they’re meeting dogs off-leash. And it’s the leash. It just it’s frustrating to them and, like I said, very common that that restraint increases their drive. And so that’s just a training component where we have to teach a dog to get lighter on the leash and to not view the leash as restraint or coercion, you know, it’s just part of the tools we wear. And once they get light on it and take those directional cues better, then all of that stuff you’re talking about gets much, much easier because they’re savvy with that information.

Will: Are there any signals that other dogs…like, the dogs are giving to each other? Because I guess the reason I ask that question is like, again, going back to personal experience, like, sometimes we’ll walk up to a dog with the lead and it’ll just be the most placid interaction ever, sniff, like, face to face and a little bit of a sniff there, sniff there, we kinda walk on and it’s all cool. Other times, it’d be like sniff, like, head to head and then all of a sudden a jump, you know what I mean? And it doesn’t look any different to me, but there must be something different going on whether or not she’s having a bad day that day, or I don’t know.

Ian: Yeah. No, that’s a really great question, Will. And so I would encourage any pet owner, regardless of what their goals are, but especially if you are going to be meeting dogs or a dog specifically, is to just be a student of canine body language. It’s really granular. You can go as deep as you want on it, but even with just a cursory knowledge of some of the most basic signals, and then getting to know what your dog’s baseline signals are. I mean, every dog and breed is a little different. But there’s definitely some signals where you can look to see that, A, maybe your dog is not enjoying the interaction or, B, the other dog is not enjoying the interaction. Their eyes, their mouth, their ears, their head carriage, their tail carriage, the way that they position their body, the way that they position their head, little signs that they do in between meetings, those are all important.

And I mean, honestly, we could go for probably hours on and I could list all the different things. But I would say one of the big things to look for is consent. So even if play looks like it’s very energetic, and it’s noisy, and it’s growly and, you know, they’re kinda bitey with each other, if you’re seeing those loose ragdoll floppy bodies, and the dogs are showing consent that when they break apart or they split up momentarily that they come back together willingly, those are all very good signs. If you start to see avoidance from one dog or another, that’s when you need to get involved because one of the party is not enjoying it very much at all.

Will: I guess that’s the thing you just need to get used to it. Especially if you’re a new dog owner is sometimes that…like, people mistake play for aggression. But you also need to be aware of when it is play and when it is aggression so that you can remove them from the situation, right?

Ian: Correct. Exactly. Yeah. Because a lot of dogs, they’re very vocal and energetic and their play, to the uninitiated, looks pretty savage. But as long as you pair them with a like-minded playmate, it’s all good, you know? But I would say, you don’t wanna check out. So one of the things I don’t like about dog parks is that people let their dogs go, and then everybody kinda just proliferates to the outside ring, and then just hangs out, you know, and they’re looking at their phones, or they’re talking to each other. And it’s, like, you’ve gotta stay involved because things can change, you know, as dogs get tired, or maybe they got stepped on, or maybe they started playing with a dog.

And then now, they’re kinda like, “I don’t really wanna play with you anymore.” And that’s when you gotta get involved, and manage, and be a good chaperone. You know, play can devolve. It can be okay at first. And then a certain dog reaches a threshold, and they’re like, “I’m kinda had enough. I need a break. This dog isn’t giving me a break.” And that’s when you be like, “Hey, you know, you go that way, you go that way,” or leash them up, or whatever you gotta do.

Will: Things can change very quickly at the dog park if you’re not careful. And you don’t really know the other dogs, right? I mean, you don’t know your own dog, or think you know your own dog, but really don’t know the other dogs at the park either.

Ian: And then it only takes one dog to change the energy of the entire group, you know? I mean, if you got, like, eight really good, easygoing, chill dogs, and then, you know, some big chili pepper walks in there and starts to stir things up, it changes the whole game all across the board. Now, one of the other things about a dog park that’s interesting that will benefit people, if you have a really high-energy, intense player, sometimes they do better in a bigger group than a one-on-one because it dilutes their energy. And that’s one of the reasons dog parks tend to get away with a lot more than they should, honestly, is because there’s so many dogs in there.

And again, we had a dog at the shelter that one-on-one was so intense that he just rubbed everybody the wrong way. But we got him in a bunch of four-way playgroups and he did great because he needed a bigger group to be able to just dilute that focus a little bit. So, you know, that’s just another one of those things to kinda consider too, just depends, I think, how intense your dog is.

Will: Makes a lot of sense, actually, from personal experience. My dog is very high-energy and one-on-one…as you mentioned, if they’re paired with another dog with similar energy and similar traits, then it’s okay. But if there’s a slight difference, if you have a dog who’s a bit more passive or fearful, it can kind of really just…it doesn’t work well. But as soon as you introduce more dogs, more stimulation, they’ve got more people to spread the fun with…sorry, more dogs to spread the fun with, it seems to, kind of, manage that situation a bit better.

Ian: Yeah, absolutely, absolutely.

Will: So if you had to wrap it up on introducing dogs, what would be your final bit of advice?

Ian: Man, a final piece of advice, that’s a good one. I would say, just look up some canine body language. There’s some really great resources out there, really accessible. Lili Chin is one of my favorites. She just published a book. And I’m not being paid to say this, I promise. I actually just love her work. And she does these phenomenal drawings that look kinda cartoony. But I have one of her posters down in my studio that I use to educate people with because it’s spot on, it is spot on. So just some good canine body language, look for consent, and then just make sure those last 12 inches are loose, man. You don’t want it tight going in.

Will: And the big thing you said earlier was the neutral ground thing. So you’re obviously better to do the introduction away from one of the dog’s homes because they might be territorial and all those things.

Ian: And resources change when you change the picture. So you may have a dog that has no resource guarding issues at all in their own home. And then you bring in another dog, you know, like, you know, my sister’s gonna come visit and gonna bring his dog. And then all of a sudden your dog is like, “Don’t touch my couch. Don’t touch my owner. Stay out of the kitchen,” you know? And you’re like, “What the heck? You’ve never been weird about stuff like this.” Well, the value of the resources changed as soon as you introduced another dog. So neutral territory just kinda wipes that stuff off the slate, at least until you get to know each other and better.

Will: We had this one experience when our dog was a bit younger. We were going to our friend’s house for the evening. We’re gonna have a dinner and then all this kinda stuff. And we went for a walk prior to going to the house with the two dogs. They had a dachshund and ours is a French bulldog. And they’re on the lead, they’re all good. They kinda met each other. And we went for this walk. And both were just kinda cruising around, smelling, and acting normal. As soon as you got back to their house, the dachshund just started barking. And three hours later, it was still barking. I was like, “What is going on here? You need to stop.”

Ian: Oh, my gosh.

Will: But I’ve come to know that dachshunds like to bark in general.

Ian: Yes. They’re a very vocal breed.

Will: Oh, yeah, yeah, yeah. Well, Ian, thanks so much for sharing your tips on introducing dogs. I’m sure there’s lots of people out there that I came to understand what the best process is to get their dog socializing with others. So thanks a lot for sharing those thoughts.

Ian: You bet. My pleasure. Good luck, everybody.

From Our Store

-

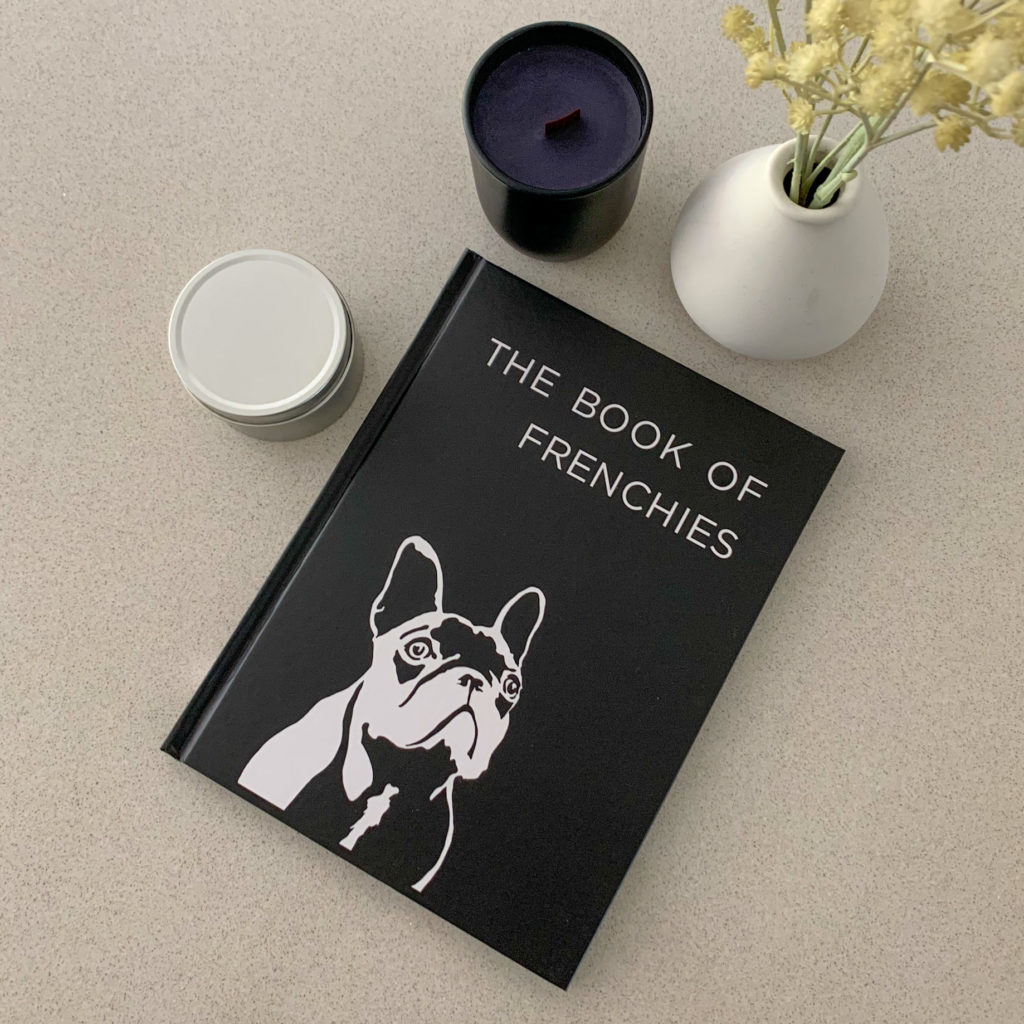

French Bulldog Coffee Table Book – The Book of Frenchies

From: EUR €33.59 Add to cart -

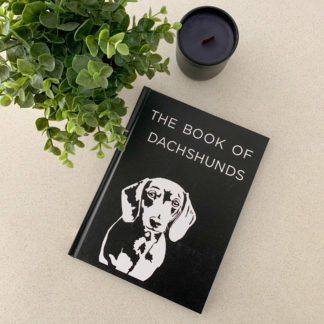

Dachshund Coffee Table Book – The Book of Dachshunds

From: EUR €33.59 Add to cart -

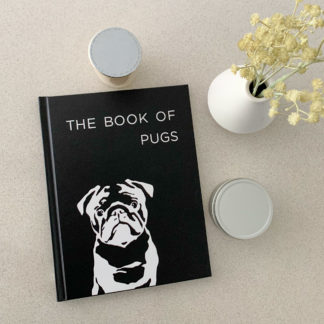

Pug Coffee Table Book – The Book of Pugs

EUR €33.59 Add to cart -

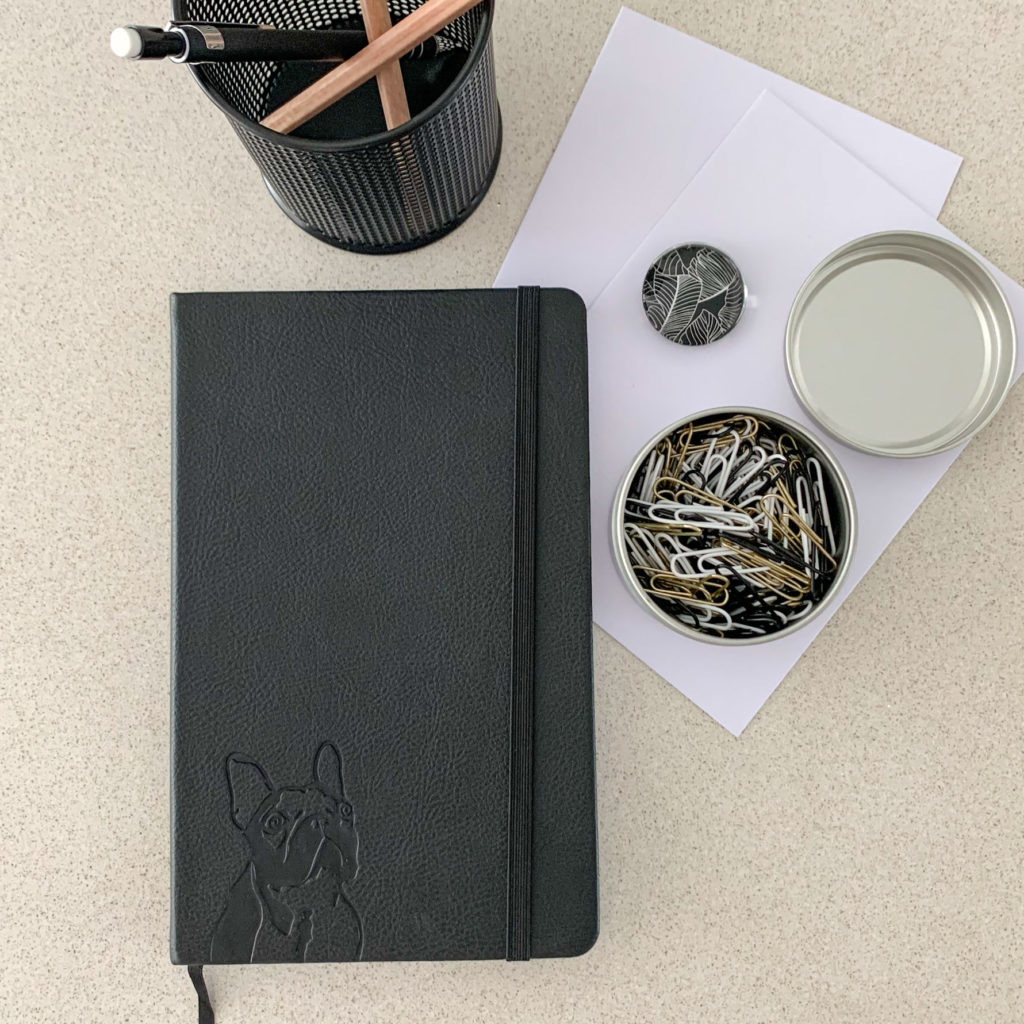

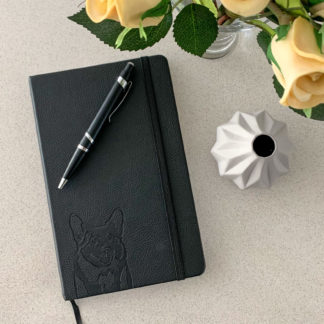

French Bulldog Notebook – A5, Hardcover, PU Leather, 100gsm Lined Pages, Bookmark (Three Colours)

EUR €19.59 Select options -

Dachshund Notebook – A5, Hardcover, PU Leather, 100gsm Lined Pages, Bookmark (Three Colours)

EUR €19.59 Select options -

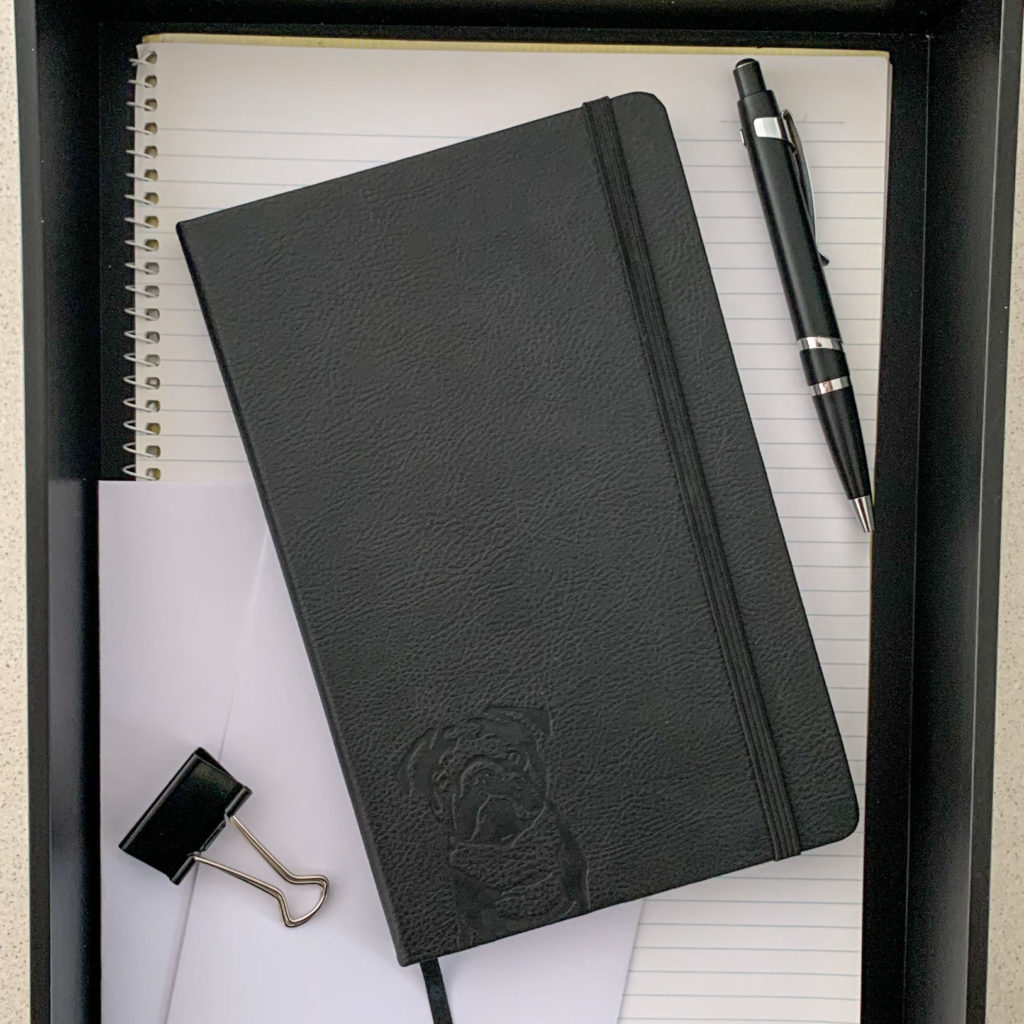

Pug Notebook – A5, Hardcover, Black PU Leather, 100gsm Lined Pages, Bookmark (Three Colours)

EUR €19.59 Select options -

French Bulldog Planner – PU Leather Exterior, Metal Loose Leaf Ring Binder, 100gsm Paper (Two Colours)

EUR €36.39 Select options -

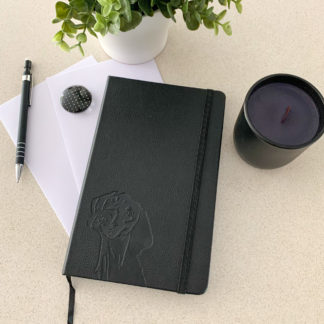

Corgi Notebook – A5, Hardcover, Black PU Leather, 100gsm Lined Pages, Bookmark (Three Colours)

EUR €19.59 Select options -

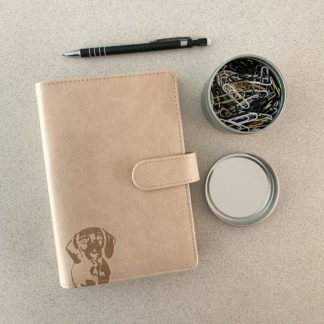

Dachshund Planner – PU Leather Exterior, Metal Loose Leaf Ring Binder, 100gsm Paper (Two Colours)

EUR €36.39 Select options -

Vizsla/Weimaraner Notebook – A5, Hardcover, PU Leather, 100gsm Lined Pages, Bookmark (Three Colours)

EUR €19.59 Select options -

Cavoodle Notebook – A5, Hardcover, Black PU Leather, 100gsm Lined Pages, Bookmark (Three Colours)

EUR €19.59 Select options -

Beagle Notebook – A5, Hardcover, PU Leather, 100gsm Lined Pages, Bookmark (Three Colours)

EUR €19.59 Select options