Do you want to learn how to train your dog to do just about anything?

This episode of The Dog Show features Robert Cabral. Robert is a canine behavior specialist whose work has helped dogs all over the world. His theories and techniques are used by animal shelters throughout the US in dealing with difficult dogs and helping to make them more adoptable. He is considered one of the top dog trainers anywhere.

In the interview, we discuss the principles of training a dog, the mistakes many owners make, and a bunch of extra helpful training tips for dog owners.

Listen

Watch

Read

Will: In this episode, I interview Robert Cabral. Robert’s a canine behavior specialist whose work has helped dogs all over the world. His theories and techniques are used by animal shelters in the United States to deal with difficult dogs and help make them more adoptable. He’s considered one of the top dog trainers anywhere. We talk about the principles of dog training, mistakes many owners make, and a bunch of extra helpful tips about training dogs for owners. I learn a huge amount once again in this episode and I hope you do too. So, Robert, thanks so much for coming on The Dog Show today. I’m really excited to interview you. Could you give me a bit of a background of your history with dogs just to kick things off?

Robert: Sure. Well, first of all, thanks for having me on your show. I’m really happy to be here. Dogs really have always been a part of my life. And so, just looking at pictures yesterday with my girlfriend and there were all these pictures of me as a young boy, like in not even a year old, several months old with my arms around dogs, hugging dogs, playing with dogs. And that was when I lived in Rhode Island. We moved to Germany for a while. The people who lived downstairs there had doxins, fell in love with them, always playing with them. And then we moved back to the States. And, eventually, we got some dogs with us. And when I lived on my own, I really didn’t have dogs for the first, like, 20 some odd years of living here in California. So, I worked as a bodyguard photographer, so I was quite busy, but I rescued a Sharpie and that was the end of it. From there on in, I just started…you know, I trained him. And then my veterinarian started getting me into dog training, referring me to clients. And from there, just had domino.

Will: Oh, that’s cool. So at the moment, you have five dogs, I think you told me. Is that right?

Robert: Yeah, we’ve got five dogs. We’ve got a German Shepherd, a Belgian Malinois, a mini Doxin, and two Labrador Retrievers.

Will: Okay. And were they all rescued or…

Robert: No. One was rescued. One was given to me by a client that was, kind of, a rescue, and the other ones were from breeders.

Will: Okay. So, do you have a…I guess it’s probably a silly question. Do you have a favorite breed of dog at all?

Robert: For me, I would probably have to say, you know, I like the herding breeds. I like Malinois…for me. I think it’s really…people always ask me that question, “What’s your favorite breed?” And it’s always a two-part question. Well, for me, it’s a Malinois, but for other people probably would definitely not be a Malinois.

Will: What’s an interesting fact about that breed that someone might not know?

Robert: Well, I think people know and they still get hooked into it. It’s just a super, super hard dog to live with. They’re very, very high drive. They’re always getting into something. They can be the best dogs in the world or they can be the hardest dogs in the world to live with.

Will: Okay. So, then they need a bit of space as well, or…

Robert: Space? Not as much attention though. Yeah, they need a lot of attention. They need to be always walked. They need to be, you know, like he’s 10-years-old and he still acts like a puppy. He still gets into stuff and whatever, you know, it’s a very high-drive, high-intensity dog.

Will: Okay. So, I guess it’s good for someone that’s always active with their dogs though?

Robert: Yeah. So, especially someone who knows how to train dogs, you know, someone who’s really skilled in it. It’s going to be a lot better dog. It’s a fun dog if you’re super involved, super hands-on, and very knowledgeable with dogs. But people get them and they say, “Well, you know, I can take them for a walk two, three times a day.” And that’s just not enough. It’s got a incredible mental and physical stimulation.

Will: Yeah, this is a bit of a left-field question, but because you’re a dog trainer, you spending every day teaching your dog things or is it about just applying disciplines every day?

Robert: Well, it’s about applying disciplines, about really being on top of your dog. It’s just something…you know, I worked as a bodyguard for many, many years, so I still sit with my…you know, I can’t sit with my back to a door. So, you know, being a dog trainer, I’m always on, like whenever I see a dog, I’m always managing the dog. And that’s not saying if they’re on their own, I’m doing it. But if they’re doing something, I’m always watching. You train a lot and I’ll take them outside and maybe work 15 minutes a couple of times a day to do something to, kind of, polish their skills and something they need to know, like a scent detection exercise or a precision exercise. But, other than that, I mean, no, you’re not really…I mean, I don’t teach them something new all the time. My dogs are very good at what they know, but I’m not the guy whose dog knows, you know, a hundred tricks.

Will: Yeah. Okay, fair enough. You mentioned briefly how you got into dog training, but how did that progress into, you know, what it is today with the YouTube channel and all that kind of stuff?

Robert: It’s so funny because a friend of mine, Jeff said, “You know, what you should do is you should put a YouTube channel together and tell them everything you know.” And I said, “Well, if I tell them everything I know, then they’ll never come to me to train their dogs.” And he said, “It’s quite the opposite. You’ll see.” And I thought, well, this is a good thing because I mean, I live in a really nice part of the country where people can afford my rates. And I thought, well, there’s a lot of people who can’t afford to hire me. And it would be a very fair gift in trying to be more altruistic to help people who can’t really afford me to give them some information for free. And if they’re willing to do the hard work of deciphering through the videos and the instruction, then I think that’s a fair gift to, kind of, give back. Because I’m really giving it to the dogs. Whenever I train somebody, I’m helping their dog, not necessarily them as much. If the dog won’t get abused, the dog will have a much more fair relationship with a person and the dog will end up not ending up in a shelter.

Will: Okay. And I guess you’ve got…it gives you a global reach as well, doesn’t it? So…

Robert: Yeah. I mean, I’ve got reach everywhere in the world. Every time, you know, someone sends me a message and it’s like I’m surprised because there’s another country that we just reached.

Will: Yeah. That’s pretty cool. I guess just to explode. So, I mean, as you said, you live in California, so you’ve got a small amount of owners and dogs that you can influence. that…

Robert: Sure. And that’s the key thing, you know, I mean, that’s why I started my nonprofit Bound Angels was to, kind of, help dogs that are in need. And that’s really the great picture of it. You know, you’re doing a good thing for people who you can reach, but there’s with one video I can reach tens of thousands, hundreds of thousands of people where teaching one person, their dog, it’s kind of like very difficult to make that same impact.

Will: Yeah. So, with Bound Angels, you’re teaching the people that work at shelters how to train dogs, so there’s less likelihood of them getting put down or is that, kind of, the gist?

Robert: Yeah, it is. So, I teach people who work in shelters, whether they’re volunteers or people who work in the shelters, trainers or behaviorist or kennel attendants. And it’s twofold. One is how to train the dogs to give them the structure, but more importantly, how to understand the dogs, how to understand a specific behavior that could end up having a dog be euthanized for.

Will: Okay. So, I guess that would be typically aggressive style behaviors and that kind of stuff or…

Robert: It can be… Aggression is one thing, but aggression is often misunderstood too. Often the dog is reactive or reactive to something that they’re not sure of. Aggression comes out of a twofold pocket. And the first one is fear and the other one is dominance. So, you know, just to understand those things better for employees gives them a better scope of how to, you know, also how to keep them safer. You know, maybe there’s certain things they’re not seeing warning signals.

Will: Okay. I was listening to one of your podcast episodes earlier about puppies and what I found interesting is you talk about the formative years and how important it is for the long life of the dog in terms of their behavior and everything like that. I guess the old saying is you can’t teach an old dog new tricks, but to some extent, you’re trying to do that in the shelters and things like that. How hard is it to teach your dog or I guess move them away from behaviors that you don’t like, such as aggression or things like that later in their life?

Robert: Well, you know, a lot of times dogs become aggressive or reactive based on their environment. So, I’ve seen dogs in shelters that are super aggressive and you take them out and they never show another sign of aggression. And I’ve seen dogs from shelters that you take out that have no signs of aggression that later develop that or, kind of, show it. So, my theory on it is a dog will, kind of, show you what it needs to show you at that moment, right? But a dog really can’t hide, like a dog is a wide-open book. Like if I look at a dog, I can tell pretty much, I would say pretty much, not 100%, but in the high 90 percentile what that dog is thinking, because dogs communicate through body language. We communicate verbally. Dogs communicate physically through body language.

So, you can, kind of, read those signals and, kind of, know what’s up with the dog. But the idea of not teaching an old dog new tricks, I think that is a misnomer because I do think you can teach an old dog new tricks. The thing is a lot of behavior, especially instinctual behaviors or hardwired behaviors, become very set into the dog. And so, you don’t undo them. You end up managing them. And that helps the dog to better understand their place in society and it helps you to better understand how to manage that dog in society.

Will: Okay. So, are you looking to remove environmental triggers, I guess, if you trying to?

Robert: You can’t, right? I mean, that’s always the thing. So, people say, “Well, my dog is reactive to other dogs. I’m just going to keep them away from other dogs.” But, you know, in today’s society that’s…I mean, now it’s easy, but, you know, with the virus, but in normalcy, it’s almost impossible. How do you keep dogs away from other dogs? There’s going to be a dog off a leash. There’s going to be a dog that’s going to bark from across the street or something like that. So, what you really want to learn is the skill how to best manage that dog, how to best figure out how to control that dog should that arise, should that kind of a situation arise. And that’s why I think management… Aggression, I really have an issue with trainers on the internet who talk about they fix aggression. If you don’t fix aggression because there’s nothing broken in the dog. When you fix aggression like a lot of people say, there’s a lot of fantastic trainers out there.

I’m not slamming all of them. I’m only slamming the cowboys who are out there saying they’re going to fix stuff. They’ve never worked with real dogs that have severe issues. But you don’t fix things. You manage them, and you kind of deal with them. It’s like a person who has mental illness. You don’t just wave a magic wand and make it better. Even if you give them psychotropic drugs or whatever that’s called, you know, antidepressant drugs, you’re kind of just masking and managing that emotion in the person. It’s the same thing with the dog.

Will: Okay. So you mentioned, I guess, that we talk through a whole bunch of different ways, but dogs talk predominantly through their body language. Is that what you said?

Robert: Yes I did.

Will: Yeah, I guess, would you find a lot of owners and I’m sure that I’m in this boat. My wife often says, “Are our dogs smiling?” I’m like, “I don’t think it’s smiling.” Did I misinterpret the behavior…the body language of dogs or…

Robert: Well, I mean, I do think dogs smile. So, that’s maybe something you want to look at because you can see a dog smiling. I mean, they do have the same smiling, kind of, mouth when they smile. What you want to look at with a dog, and I talk about this a lot in my workshops, this is mainly with shelters I’m talking about here, is look at the whole dog, right? So, a dog could be wagging its tail and you go, “Oh, he’s happy, he’s wagging his tail.” And he’s going to bite somebody, because you weren’t looking at the ears being pinned back or the hackles being up on the dog. Really with a dog, the only picture you need to get of a dog is the whole picture. Individual pieces don’t necessarily mean anything.

Will: Okay. So, back to training for a second. Do you have a set of principles you follow when trying to train a dog something? Do you want to take the time to do that?

Robert: Yeah. My saying is everything I do with the dog starts with a toy and a treat and where it goes from there is up to the dog. So, everything in my philosophy of training, a dog must start with, one, a relationship and, two, a desire of the dog to want to please me. So, I want the dog to first of all look to me as somebody he wants to be with, he wants to do something for. And then, two, I want to give him a reason to do that. That means there’s a reward. That can be a treat. It can be a toy, it can be a pat on the head, it can be an attaboy or anything like that. But that’s where everything must, must start with the dog. You know, we can take a dog that maybe has some, you know, an aggression or reactivity issue, if it’s dominance-based, and use more of a compulsion or a correction on the dog to get it to not do it. But what we really want to do to train a dog is to form a relationship and form habits, form behaviors on the dog, and then use those and put them on cue.

Will: Okay. So, would you say how important is like repetition and everything like that when you’re trying to teach a dog something?

Robert: Huge. You know, I think the biggest failure of people is that they end up giving up too soon. I’ve had dogs where it took me an entire 40-minute session to get them to lie down with using a treat to get a proper down. And, I mean, I could have done it with a prong collar on an electric collar or yanked them down or done that, but I didn’t really think it was necessary. Now that’s not saying I’m against prong collars e-collars or anything like that. I think every tool has a place for a dog, but I think most tools are just, you know, it’s a generic tool. It’s like I get a remote call and a bit gets a remote call and they start pushing buttons, pushing buttons. That doesn’t solve the problem, right? It’s not a remote control dog. It’s actually a living, breathing, thinking, a being that has feelings and emotions like us.

To train them, we need to connect with them. And I think that’s, kind of, void in a lot of training methods, whether it’s the all positive or the all compulsion. I think these trainers are overlooking the cognitive, the mental aspect that the emotional aspect of the dog and just thinking, “I said, ‘Sit.’ You got to sit. And if it’s not working with a treat I need to get a different treat.” No, there might be a reason the dog is not sitting, right? The dog might not be clear on what you want him to do. The dog might have an ache or a pain or the dog might be uncomfortable or fearful or dominant. Those are things we need to look at when we examine the whole dog and that’s what any good dog trainer is a master at doing this, figuring that out. It’s communication.

Will: Does a dog forget something because I guess if they’re not doing it regularly or is it if you teach a dog, you know, to lie down or to sit or whatever it is, they seem to, kind of, remember that for a long, long time.

Robert: True. Well, I mean, people forget things too. You know, it’s the exact same thing. And when you look at any mammal…

We forget things, but if we’re reminded then we remember it more quickly than if we’re first taught it. Exact same situation with the dog. You know, really you got to look at the dog, and I think this is one of my main things I try to preach in my lectures is please understand that the dog is an emotional creature. He might be having a good day. He might be having a bad day. He might be happy. He might be sad. He might be stubborn. He might be easy. But those are all things you’ve got to look at and understand when you work with a dog.

Will: Yeah. How much variance is there between different breeds? I mean, you hear people talk about smarter dog breeds, like your German Shepherds and things like that, but when training a dog, how much variance is there?

Robert: I mean, there is, it’s not…you know, they say the Border Collie and the Malinois are the most intelligent dogs, which I probably would agree with. But what you really looking for in a dog is the bit of the liberty of the dog. So, how willing is the dog to work with you? You know, you could have a super-smart dog, like a Border Collie and it’s very, very difficult to train because it’s so smart. It’s actually out thinking you. There’s been times where, with Goofy, he knows hand signals and verbals on things like, “Sit down and stand.” Well, if I move my hand a certain way, he predicts something’s coming and he might do something I don’t want him to do. So, he’s already out thinking me. Whereas a dog that’s more simple and more biddable, like a Labrador Retriever, is oftentimes an easier dog to train because they’re, kind of, just saying, “Okay, make it clear what you want.” And then they’ll do it.

But it’s a tough one. It’s a real tough line because you don’t want a dog that’s completely, you know, like hounds for example, they’re more stubborn and aloof dogs than gun dogs like retrievers or herding dogs. And you, kind of, want to go into the groups of the dog, as opposed to the individual breeds, because that’s going to give you a better picture. So, like is a German Shepherd and a Border Collie and a Malinois intelligent while they’re all three members of the herding group? And the reason they’re in that group is because they work well at a distance. They work well in looking at relating to a person where a retriever works much better on their own. They’re set out, they’re going to go out, they’re going to get the bird, they’re going to come back with a bird unless I blow a whistle and tell him to do something different. They’re not looking for any interference, where the herders are always looking for, “Now what? Now what? Now what?” It’s a different relationship.

Will: Okay. I’m going to give you a real-life scenario here and I’m interested to hear what your thoughts are on it.

I have a French bulldog. My wife and I have a French bulldog. She’s four years old now and she has a…like I think she has an amazing personality, very loyal, you know, doesn’t show any…like great with kids. She’s grown up with kids and all kind of stuff. One thing that we struggle with still, and it’s probably because we didn’t socialize it with other dogs enough when she was younger, I think, that’s my assumption, maybe I’m wrong, is we’ll take it to the dog park and for the most part she’ll be good. Like she’s very energetic, loves jumping, bounding around, jump, like playing with other dogs. But it’s almost like she picks out the dogs that don’t want to play with her, and like goes over to them. And if they don’t give her attention, she’ll kind of jump at their face a little bit, like she’s not trying to bite them or anything like that, but like she’s basically trying to piss them off until I do something that’s, sort of…it’s like, what would you do in that situation?

Robert: Well, I strongly caution people to stay away from dog parks for, and it might be different in Australia where you are or in your particular area of Australia, but for the most part what happens in dog parks is dogs that don’t know each other are vying for position and trying to develop a hierarchy, right? Which happens anywhere you go. And if you go to a bar, you’re trying to figure out, okay, who’s the tougher guy? Who’s this? Who’s that? Because it’s more so with dogs because dogs are much more primal than us, but they’re constantly looking for that. Even in play, the reason dogs play is because they play in a methodology that would help them to fight. Just like if you watch a lion cub, you know, playing, they’re playing in a way that, “Okay, I’m practicing my fighting skills.” That’s what predators do.

So, when you take a dog to a dog park, and I’ll get back to the question of your dog, but when you take a dog to a dog park, that jockeying for position is always, kind of, going on to some degree or another. Now, people who go to a dog park who…you know, I’m meeting five of my friends with five dogs we know at a dog park, I got no problem with it. I think dogs are very social animals and they enjoy their interaction with each other. Whether you have five dogs in your own home or you’ve got a bunch of friends, you may put together a group of dogs. The issue comes in when there’s unfamiliarity and a difference of temperaments, some dominant dogs, some aloof dogs, some fearful dogs. And then that comes together and a fearful dog sees the dog jumping in their face as a threat and will bite.

Where a really clear-headed dominant dog sees you jumping in his face and he’s like, “You know what? I’m just not going to do this.” And he’s going to blow it off. So, when you have your dog doing that, yeah, obviously she’s looking for something to instigate or to initiate because it’s something that’s not normal. “Everybody else is playing whether you’re not playing, why aren’t you playing?” And she susses that out. And Frenchies are super cordial with people. They’re super fun. They can have aggression issues to people because they’re so babies and cute. So, they never really learned that structure. And that can be with any dog, right? That’s not just alone to a friendship, but usually, dogs that are more lapdogs or really cute-looking dogs that attract a certain type of owner who is just going to calm them and baby them, well, they’re going to have more of that issue than a dog that’s given structure through its whole life.

Will: Okay. So, I guess what you’re saying is you’re better off to socialize dogs in an environment where you know the owners, you know the other dogs. There’s some sort of comfort level there. More so than going into a park where there’s all sorts of different dogs that you don’t really know.

Robert: You want to remove the variables. So, you know, people always say that. I did a program where I taught shelters, animal shelters, how to put together playgroups and I did it very different. I think maybe two of us in America are really doing the playgroups in a certain way. Two organizations, one is Bound Angels and there’s another one. And my methodology to putting dogs together in playgroups is very strict. It’s very hands-on. It’s very structured. I never let the dogs work it out because I think dogs make bad decisions. So, what I do is I structure the introduction and I structure the interactions. And my partner and I who did the program, we would have between 10, 15, 17 Pit Bulls, big Pit Bulls, powerful dogs in one yard at one time. Dogs that had never met before. And we could do that because we completely manage the situation.

So the dogs never had an opportunity to do something stupid, right? I mean, it’s a bad word to use, but they really never had a chance to jump in somebody’s face. Because the minute they did, we were on top of them. “Tom, Hey, knock it off.” And people say, “Well, you’re micromanaging the dogs. You’re doing this. You’re doing that.” But in 10 plus years of doing that, I can honestly say I’ve never had one serious injury that even required one stitch. Yeah. And nobody can say that. No other organization can say that. No other trainer can say that. But it’s because he and I managed this program in a way that the dog had a great time, right? They didn’t only get to play, but they learned a skill that will keep them alive and get them to play more. So, it’s controlling the environment.

Will: Yeah. That’s helpful. Thanks for that advice. Apologize for jumping down my own path, but I’m sure it will be helpful for other people out there about socializing the dogs and dealing with that behavior anyway.

Robert: Yeah, please keep them out of dog parks because once a dog…you know, if you have a really good natured dog and he gets nailed by a dog really hard, especially early on, that dog will always have this suspicion in his mind. And that suspicion will lead to fear or dominance. And people don’t want to believe it, but I’ve trained a lot of dogs in my time and I can tell you that dogs that have had negative interactions with other dogs early on usually end up not being the nicest dogs.

Will: Yeah, that’s interesting because we actually had an experience when our dog was a puppy. We had a Labrador that was staying at our house for a few weeks, a friend’s Labrador and it was a lot older, eight years old when we like our dog was, you know, six months old. And it showed quite a lot of aggressive tendencies towards our puppy, growling, kind of not being very interactive. And obviously the puppy just wanted to play the whole time. And we often wonder. We had to separate them. Ended up like sending the dog back to another friend to look after because it was, kind of, at that point that they had to be fully separated. We weren’t sure what was going to happen. So, I mean, I wonder if, and like an experience like that could have influenced the behaviors as she’s got older.

Robert: It could have. You know, it could have, I mean, look at people who are emotionally or physically abused as children usually turn out to be, you know, very different than people who weren’t.

Will: Okay. So, if you had to give our listeners one big takeaway from today’s show, what would that be, do you think?

Robert: Learn to understand that your dog is a living, breathing, thinking, emotional creature. It’s not an object, right? It requires structure first. Dogs see life through structure, then love. Humans see life through love, then structure. And give a dog a fair chance because all the work you do with your dog, all the training you do, all the structured interactions you do will help that dog live a very, very happy life. And the dog will die in your arms as opposed to on a cold table in a shelter. And that’s been the core of my mission is to make sure that dogs stay with their families forever. And that more structure you give them, the more interaction you give them, and the more you understand that it is a living, breathing creature with its own set of emotions and feelings, then you’ll have a much better chance of giving that dog. You know, you’re the custodian of that dog. You got to give it the best chance you can.

Will: Great advice. So, structure first, love second. Great advice, great advice. So, where can people find more about you, Robert?

Robert: Well, the easiest way is if you go to my site, robertcabral.com, there’s links there to my YouTube channel, my membership section, my Bound Angels, every single thing is just on the front of that page.

Will: Yeah. And I highly recommend checking out the YouTube channel. It’s very, very helpful. So, thank you. Thanks so much for coming on the interview today. I really appreciate your time.

Robert: Thank you so much for having me.

From Our Store

-

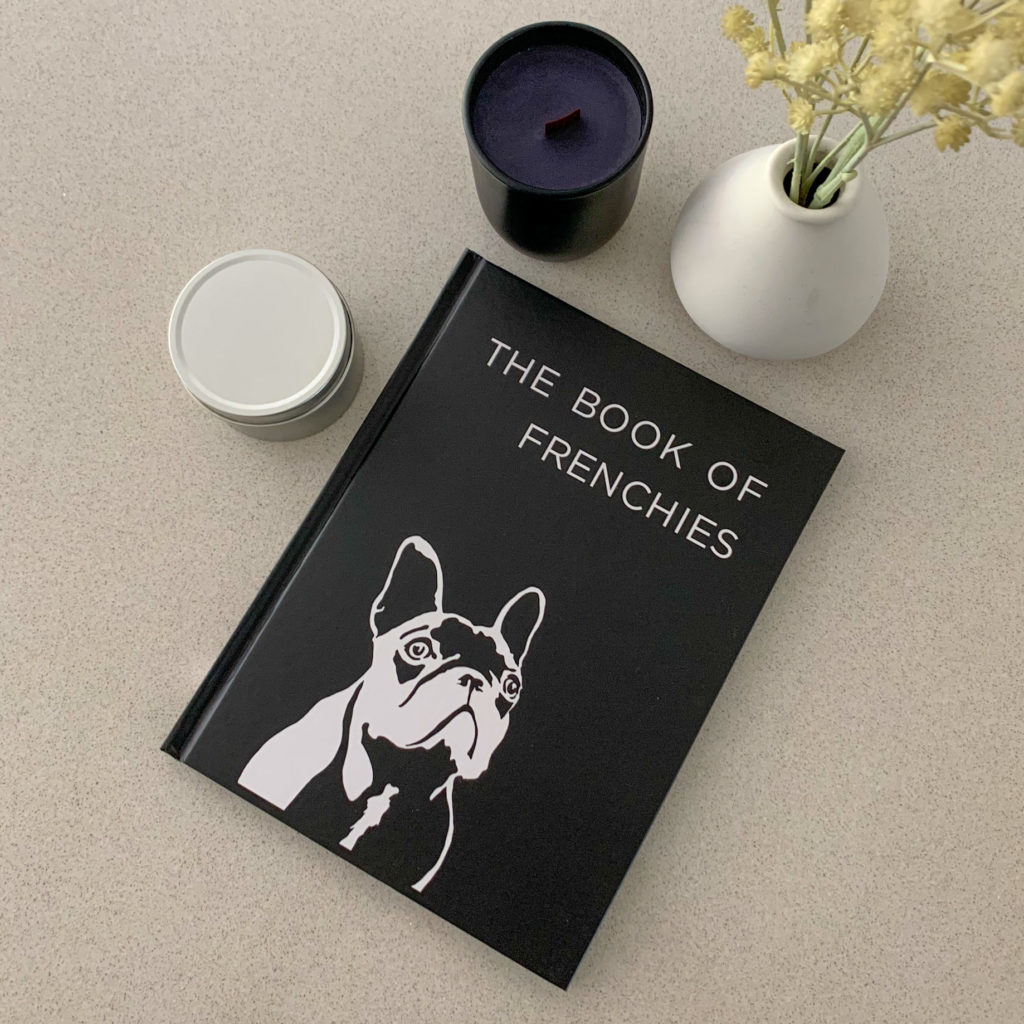

French Bulldog Coffee Table Book – The Book of Frenchies

From: EUR €33.53 Add to cart -

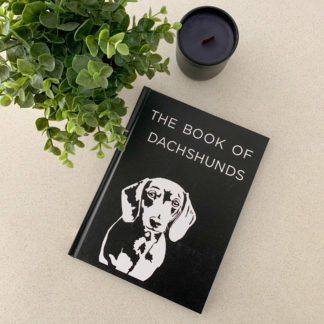

Dachshund Coffee Table Book – The Book of Dachshunds

From: EUR €33.53 Add to cart -

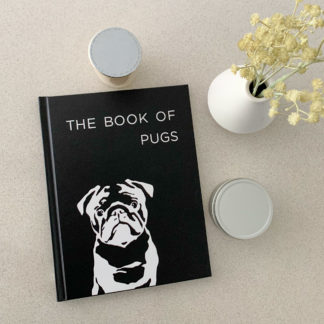

Pug Coffee Table Book – The Book of Pugs

EUR €33.53 Add to cart -

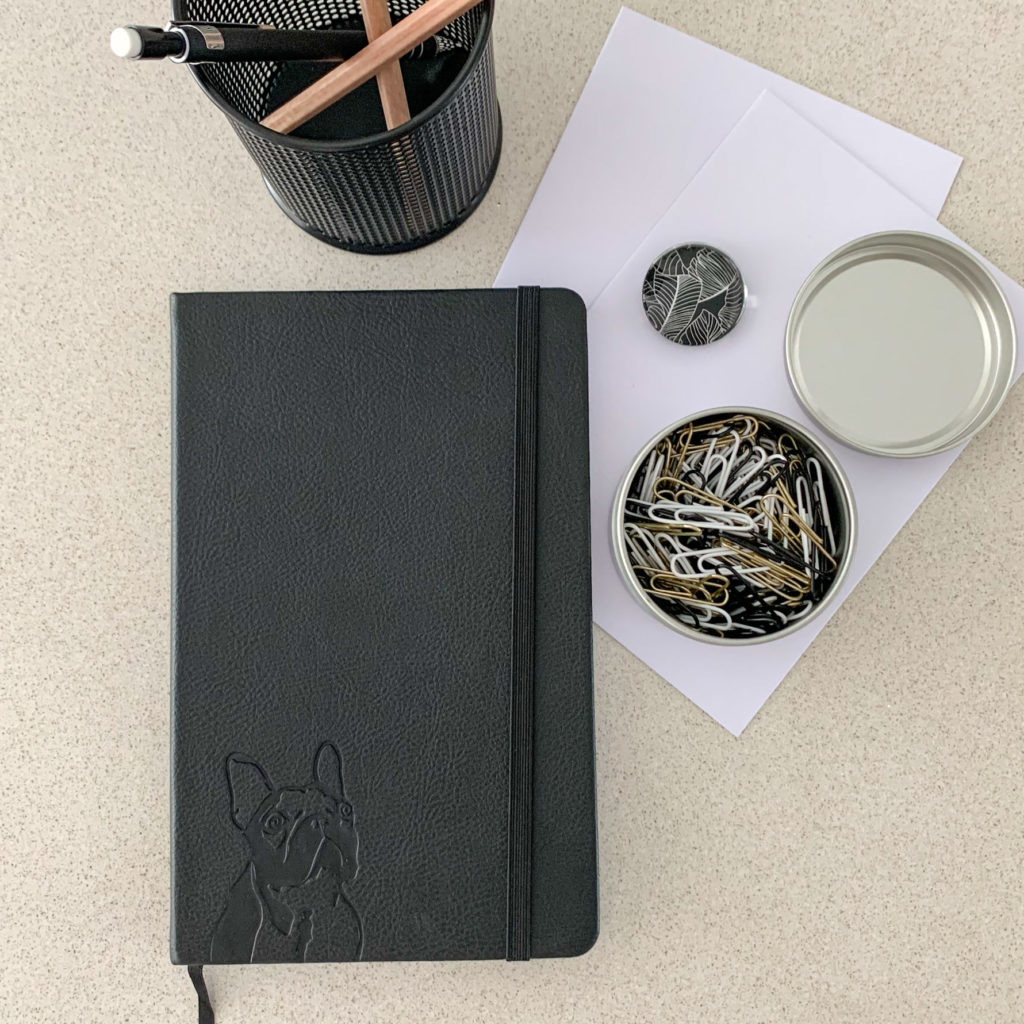

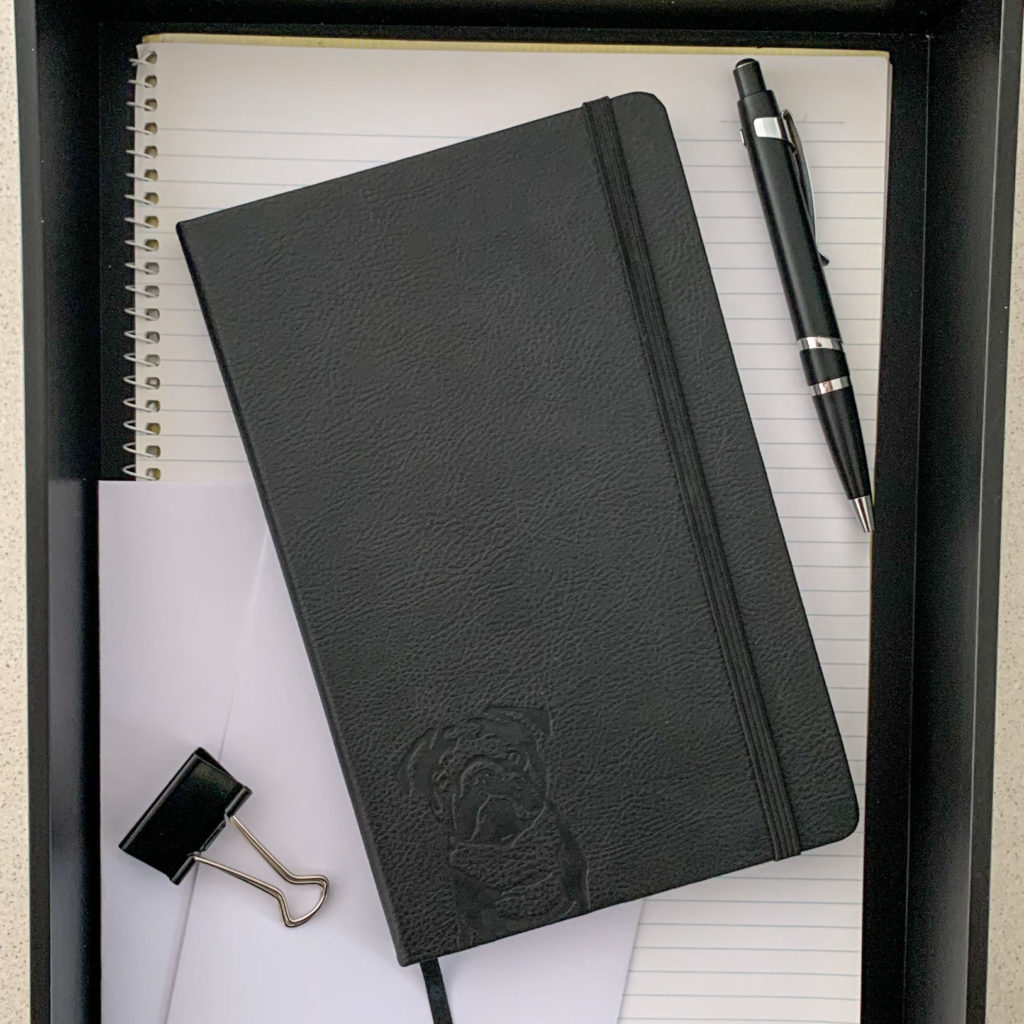

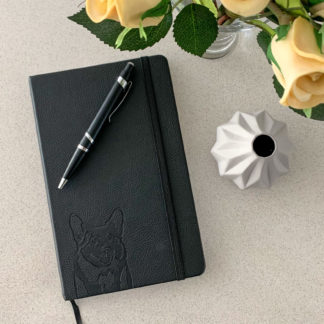

French Bulldog Notebook – A5, Hardcover, PU Leather, 100gsm Lined Pages, Bookmark (Three Colours)

EUR €19.56 Select options -

Dachshund Notebook – A5, Hardcover, PU Leather, 100gsm Lined Pages, Bookmark (Three Colours)

EUR €19.56 Select options -

Pug Notebook – A5, Hardcover, Black PU Leather, 100gsm Lined Pages, Bookmark (Three Colours)

EUR €19.56 Select options -

French Bulldog Planner – PU Leather Exterior, Metal Loose Leaf Ring Binder, 100gsm Paper (Two Colours)

EUR €36.33 Select options -

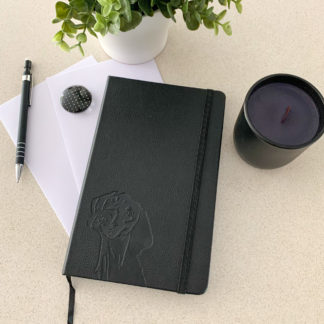

Corgi Notebook – A5, Hardcover, Black PU Leather, 100gsm Lined Pages, Bookmark (Three Colours)

EUR €19.56 Select options -

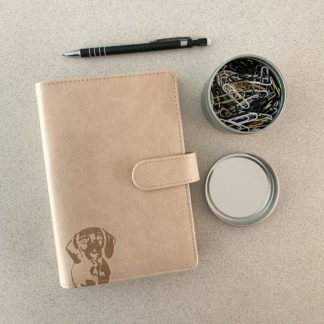

Dachshund Planner – PU Leather Exterior, Metal Loose Leaf Ring Binder, 100gsm Paper (Two Colours)

EUR €36.33 Select options -

Vizsla/Weimaraner Notebook – A5, Hardcover, PU Leather, 100gsm Lined Pages, Bookmark (Three Colours)

EUR €19.56 Select options -

Cavoodle Notebook – A5, Hardcover, Black PU Leather, 100gsm Lined Pages, Bookmark (Three Colours)

EUR €19.56 Select options -

Beagle Notebook – A5, Hardcover, PU Leather, 100gsm Lined Pages, Bookmark (Three Colours)

EUR €19.56 Select options