Are you worried about puppy biting or chewing?

This episode of The Dog Show features Ian Stone. Ian is the owner and principal trainer of Simpawtico Dog Training.

Simpawtico uses intelligent and creative training techniques to help you manage, motivate, and learn about your beloved canine family members.

Ian also has a Master’s degree in teaching from Southern Oregon University and lives with his wife and four dogs in upstate New York.

In the interview, we talk about why puppies bite and chew, the importance of understanding bite force with your dog, and some tips on how to stop your puppy biting.

Find out more about Simpawtico Dog Training here:

Listen

Watch

Read

Will: This episode of ”The Dog Show” features Ian Stone. Ian is the owner and principal trainer of Simpawtico Dog Training. Simpawtico uses intelligent and creative training techniques to help you manage, motivate and learn about your beloved canine family members. Ian also has a master’s degree in teaching from Southern Oregon University and lives with his wife and four dogs in upstate New York. In the interview, we talked about why puppies bite and chew, the importance of understanding bite force with your dog and some tips on how to stop puppy biting. So Ian, welcome to ”The Dog Show” today. Thanks very much for coming on.

Ian: Thank you, Will. Thank you for having me. I really appreciate it.

Will: Yeah. Great. So you grew up with a Chow Chow, I believe, named Hotai?

Ian: Yes, sir.

Will: And today you have a, you know, a huge clan of dogs from Bulldogs, Boston Terrier, Jack Russell. Can you tell me a bit more about your history with dogs and why you’ve got all these different breeds and why you love them?

Ian: Oh, sure. Yeah. I mean I grew up, you know, with I had Chow Chows the whole time I was growing up and one Norwegian Elkhound, which are, you know, especially with Chow Chows, they’re not typically, you know, you would consider, what many people consider family dogs or childhood dogs. And it wasn’t until I was a lot older when people were like, “Oh, Chow Chows.” Yeah. And I’m like, “What? What are you talking about?” You know? I mean, they were always wonderful, wonderful, wonderful dogs and Hotai was definitely my buddy. But I went, you know, after I moved out of my parents’ house and went to college and you know, just kind of started my own life, I went a long period without a dog. I just, you know, I was moving around the country. I didn’t really have time for a dog. I was like, “Ah, you know, no. I don’t really need a dog,” even though I was a huge dog person growing up. I mean, just, I mean, I remember going to my, when I was 16 going to my girlfriend’s birthday party and like met her dog in the driveway and like a half hour later, everybody comes out and like, ”Are you coming in or what?” You know, because I’m still hanging out with the dog.

So I went a lot of years without a dog in my life. And then when I was in New York, I moved out to New York, Upstate New York and I kind of settled in, you know, had a nice house and stuff. And then I remember like I saw a bulldog hanging out of a window of a car and I just, I remember thinking, “I really like bulldogs. I think I’m gonna get a bulldog.” And that was that. That’s actually Dexter my bulldog. He’s almost 13, which for a bulldog is ancient.

Will: Yeah. That’s a good innings as I’d call it. That’s probably in a cricketing term though. So I’m not sure if you’re familiar with that.

Ian: No, but yeah, the metaphor absolutely holds up. And he’s still trucking along and that really kind of reignited my whole passion and love for dogs. And here I am, I got two bulldogs and a Boston terrier. I love Boston terriers, actually my third Boston Terrier since then and my Jack Russell. And my Jack Russell is actually how me and my wife met.

Will: Right. Yeah. How did that happen?

Ian: Well, so when I started dog training, one of my very, very, very first group classes I ever did was a small class. There’s a whole story that I could go into about my wife, but long story short, I had seen her around town. I thought she was really cute, but it was just one of those things like, you know, that’s that. And then when I started dog training on my own and I started running a class, the very first person that signed up for my very first class was her, with her Jack Russell. Yeah. And so she went through a couple of classes and kept coming back and, you know, we started talking, we had a lot of commonalities and things we liked and it was just like, “Well, you know, we should hang out one time.” And then she was like, ”Well, here’s my phone number.” And that was that

Will: Well, for people out there that are, you know, looking for love, I guess, there’s some advice, like connect via your dogs, I guess.

Ian: Oh, for sure. Yeah. Yeah, yeah. That’s it. Yeah. If you like dogs, that’s a sure win, yeah.

Will: It actually is a great way to, you know, start a conversation with someone. Like, if you’re a dog person, right, and you’ve got a dog or someone else has a dog, it’s just in an immediate kind of way the chat, but.

Ian: Oh, sure. Yeah. Yeah. You’ve just got something right away in common, you know, and there’s a lot of things you could disagree about, but most people that are dog people are always, you know, right on the same page.

Will: Yeah, yeah, yeah. Actually, I mean, I’d usually dive a bit deeper into the different breeds that we’re discussing, but there’s so many going on. I guess I’m most intrigued about the Chow Chows just because of their look, and I guess they’re a little bit more, they’re a little bit rarer than, you know, your bulldogs and stuff like that as well. What are their personalities like? Is there anything that, you know, most people wouldn’t know about a Chow Chow that you could share?

Ian: Well, I’d say most of what I tell people about Chow Chows is gleaned from my experience as dog trainer, right? So if I hadn’t had any dog training or behavior experience and, you know, we were just on the street and you’re like, ”Oh, you love Chow Chows. What do you think?” I’d be like, ”Oh my God, they’re fantastic dogs.” But that was just my very limited experience. You know? And even though I didn’t know anything, I was just a kid. My parents didn’t really know anything about dog training. Like, somehow we managed to cultivate these really wonderful family oriented, friendly tolerant Chow Chows. But those are not adjectives that are normally applied to Chow Chows. You know, they’re very, usually they’re kind of persnickety, they’re stoic. They can be very selective with the kinds of people that they bond to. And I have definitely seen that with Chows than I worked with either in my practice or, you know, in my work with the shelter. You know, I would not say that they were breathing normally recommended for first timers. They’re kind of an interesting, tough nut to crack. So, you know, they require a lot of patience, a lot of structure, a lot of routine and a lot of good trying to cultivate that friendly outgoing dog because they’re just, you know, they kind of live up to the mythology. They’re an interesting breed that’s just not for everybody. So I think I was very fortunate growing up.

Will: Yeah. It sounds like you had a good run, but you know, what I’m hearing is that if it’s your first dog or you’re thinking about getting a puppy, it’s probably not the best one to, the best breed to be looking at, to start with because it could be a lot of work and require a lot time.

Ian: And then, I mean, you have all the personality issues that go with the Chow Chow. But the other thing with Chows is that they have a tremendous coat. So there’s a lot of upkeep with them too. I mean, we’re talking regular brushing, grooming appointments and just like any of those dogs with coats like that, like you have the summer blowout and, I mean, it just comes off in sheets. So if you are going to get a Chow Chow, you’re gonna have your hands full on several different fronts. So just, you know, buckle your seat belt, be prepared.

Will: Yeah. I imagine their coat is more suited to a cold climate as well. Would that be fair to say or?

Ian: Yeah, cold or temperate. I mean, the blowout is they get pretty lean as far as the coat goes in the spring and summer. So they do okay. But, you know, in a really hot climate, like in Arizona or something like that, they would definitely struggle.

Will: So do you think you have a favorite dog breed? I guess you’ve had exposure to so many through your work and then you’ve also owned Chow Chows, bulldogs, Boston Terriers. Seems like based on your ownership as you’ve got older with the bulldogs and the Boston Terriers, it seems like you’re leaning that way. Is that fair to say?

Ian: I really am. You know, I mean there’s been tons and tons of dogs that I love to work with. I mean, I love new Norwegian Elkhounds. I love all the working breeds. I love Malinois. I love working with them, you know. And I know as a trainer, you know, the kind of expectation is you’re supposed to have a Husky or a Border Collie or a German Shepherd or a, you know, one of those kinds of things. And I’m just unapologetic. I love short nosed, snotty, farty, goofy dogs. I just, I can’t get enough of them. I just can’t. They’re hilarious, they crack me up, they make me smile, they make me happy, and I think it’s really neat when people see well-trained versions of those dogs you know. I think people just don’t expect it. You know, they’re kind of like, “Ah, that’s a lazy, you know, snotty dog with not a lot of stamina. They just do what they do. They lay around all day,” you know. And then, you know, my dogs, the heel and come and walk around off leash. And I think that’s kind of neat to have dogs of those breeds styles do that kind of stuff. And I just can’t get enough of them. I just love them.

Will: Well, I guess it’s a point of difference for you as a trainer as well if you’ve got a lot more experience with those types of dogs compared to, yeah, as you mentioned though, the Collies, Border Collies or the German Shepherds and stuff, which a lot of traditional dog trainers work with. Yeah, you’ve got like that point of difference there and I guess people that, you know, there’s, I mean, bulldogs are very popular dogs and other small dogs like that are very popular dog. So if they’re facing issues, then your expertise can really help out.

Ian: Right. Yeah. And I think that’s, I think you, I definitely take that to heart. As you’ve said, I think that’s part of my angle as a trainer, you know. So you kind of get this focus in the training community, and I think in pet owners in large that like, okay, well, if I have a German Shepherd, I have to do X amount of extra training. Or, you know, if I decide to jump into some kind of a working breed or a sporting breed, a pointer, or, you know, something like that or a heeler, you know, when you have all this extra stuff to do. And I think many people don’t realize that terriers, for example, are that same amount of intensity and require the same amount of structure and training, but because they’re smaller, kind of scrappy and sometimes yappy and even sometimes kind of neurotic, you know, that kind of gets forgotten, I think, in the general wash of training information. And so, you know, with my Jack Russell, that’s another breed that people are like, “Oh, a Jack Russell,” you know, and there’s all the mythology like, “Oh, they’re so scrappy and they’re so crazy energetic and stuff.” And I’m like my Jack Russell’s a community good citizen, like he’s several levels up above. And so I think taking a terrier, whether it’s a Boston Terrier or a Jack Russell Terrier or a Westie, or, you know, a Scottie or a Russian Terrier or any of these kinds of cool breeds that are crazy and energetic and scrappy and people struggle with and say like, “We can do it. We can do it.” I think that’s important to have. And I love terriers. I love their energy. I love they’re scrappy. I love that they’re kind of bananas and running around, jumping off the walls. And I guess there you go, that’s my thing, it’s the terriers and the short nose snorty dogs.

Will: Yeah. Well, I’ve got a French Border myself and you get a lot of that, the bulldog, like the snorty and the farting and the laziness, but they’re high energy dogs as well like they run around bouncing off the walls, like pretty much as much as you allow them to, so.

Ian: Yeah. Yeah. And Frenchies got some sass too, you know, and they’re kind of like, “Well, I don’t really wanna do that right now. What are you gonna do about it?” You know? And you gotta pull more tools out of your back pocket than you would with, you know, some of those other more agreeable breeds.

Will: Yeah. Yeah. Okay. So how did you get into all this stuff? I mean, you’ve got like this amazing online platform now, like over 200,000 YouTube subscribers and all this really great content and everything. But how did that all start? How did you get into it to begin with?

Ian: I spent a lot of years as a actually high school teacher and I traveled around and worked in a couple of different States as a high school teacher, and then I was doing illustration graphic design freelance on the side. And those were my two main gigs. That was really it. And then when I moved to New York, I went through a really bitter divorce. I mean, it was just savage. And as those things, do, you know, my mental health just went in the toilet. I wasn’t sleeping. I was hallucinating at work. I wasn’t eating. I was just tons of stress. And so consequently, I ended up leaving the teaching profession. And so now I find myself I’m stranded in New York. You know, my ex has gone back to the West coast. I have, you know, bills, I’m suddenly out of a well-paying job, and what do I do? So I just started putting out applications to places just to start getting some income and start paying the bills and getting back on my feet. Well, one of the first places called me was a PetSmart, right? So I went in, interviewed, interview really well. And they’re like, ”So you have a teaching degree. Like, you have teaching experience. Well, we need a dog trainer. Like, what do you think of that?” And I’m like, ”Yeah, that actually sounds like a lot of fun.”

And that was that. I mean, back then PetSmart’s program, their training program was way more robust. You know, it was good practicum. There was a long period of internship and kind of apprenticeship. And then I got cut loose on my own. I was the only trainer in that store, built up a really good reputation in the community and in the business. And I did that for probably I think, five years. And then, you know, I just got to a point where my abilities as a trainer and my interests as a trainer were starting to grow beyond what that corporate world would be. And PetSmart had been bought by another company, and so, you know, their adherence to training and their support was starting to really kind of crumble and break down, and I was just not happy with in any way. So I took that, you know, my reputation in the community and I just took a plunge and I just quit and the very next day started my own business and it’s just been like wildfire. It was the most, simultaneously the most rewarding and hardest thing I’ve ever done. So it’s great.

Will: Yeah, I feel you. So do you think teaching background, because you got a master’s in teaching, right? Do you think that’s helped with dog training?

Ian: Absolutely. Absolutely. Because, I mean, you know, when you learn to be a dog trainer, there’s a huge portion of learning to work with the dogs, you know, so you learn methodology, you learn etiology, you learn strategy, you learn procedures and tactics and all that kind of stuff when working with the dogs. But, you know, you get to a point as a dog trainer when working with the dogs. It’s really easy, you know, and you do it a few years ago, like the dogs are easy. So good dog training is actually teaching their owners. And that’s where I think coming in with that teaching experience has tremendously helped me out because you know, now I’m approaching my lesson design like a teacher instead of a trainer. So yeah, absolutely.

Will: I just had a light bulb moment. I’ve been speaking to people for a while now about behavioral issues with dogs and training dogs and all this kind of stuff. And the whole time, my frame of reference has been thinking about what the dog needs to do. But there’s another side of my brain, which is thinking from a personal perspective, I know the biggest challenge is me and my wife not being able to actually, you know, fulfill the discipline that’s required to actually help them change their behavior. So that was a real light bulb moment what you just said then, like, you’re essentially teaching the owners what they need to do. So if they’re not gonna be good students, then the dog won’t learn.

Ian: Correct. Correct. Yeah, yeah, yeah. Yeah. And, I mean, any trainer worth their salt that’s been around for a long time, you know, will tell you that here comes problem dog A. While I’m working with a problem dog, they’re fantastic. And then they go home and the problems continue. So what changed? How they’re being handled and managed, you know. And that’s where we have to put the focus is I gotta get buy in from their owners. I gotta help the owners feel comfortable with the protocols and I have to help the owners understand why we’re doing things. And then I have to, as a good instructor, I have to coach them well enough that I feel confident that when they leave me, they have the tools to be able to continue. And that’s, yeah, that’s the challenge.

Will: Yeah. Yeah, absolutely. Well, I appreciate you sharing a story about how you got into the industry, because I think dog stuff aside, it’s quite a powerful and inspirational story for people out there because I mean, you’ve obviously had some hardship and like had to discover what you were passionate about and what you really loved and found your way out the other side as well.

Ian: Yeah, for sure.

Will: So a lot of people can draw inspiration for that I’m sure.

Ian: I hope so. Yeah. Yeah, no, it’s definitely discovering as kind of a second career, so to speak because just, you know, if I was gonna go back and do my life over, I would definitely just start with this.

Will: Yeah. Oh yeah. Isn’t it funny when he gets to that point? And I absolutely love what I do now with like working so much with dogs and stuff, but in a similar way to you, I mean, I went through years and years trying to figure out what I wanted to do with my career and working in different jobs and stuff. And when you actually start finding something you love, you’re like, “Wow, I wish I’d I know this 10 years ago,” but.

Ian: Absolutely. Absolutely.

Will: I think it’s especially prevalent at the moment with everything that’s going on in the world too. So I’m sure there’s a lot of people that are reaching a point where they may need to adapt or change, do something different, so.

Ian: Definitely. Definitely. Yeah. And I think it’s gonna be that way for a long time, you know.

Will: Yeah. Seems that way. Like it’s, you know, people have gotta change the way they, I mean, work’s changing, life’s changing. And I guess that actually leads me into my next question. So because of everything that’s going on at the moment, there’s been a real uptick in people buying puppies as companions and things like that. And many of them are new owners, which we kind of briefly touched on earlier, who maybe they don’t know what they’re getting themselves into, almost definitely don’t know what they’re getting themselves into when they get a new dog.

Ian: For sure.

Will: But what a common problem that new owners face and the question that I regularly get asked is, you know, “My puppy’s biting or chewing a lot. What do I do about that or why they doing that kind of thing?” So why do you think that’s such a common, I guess, curve ball for new owners to face?

Ian: It really is. And it’s, you know, it’s very astute that you’ve pointed that out in the I was gonna say in the industry, I’m not sure that’s the right word, but just that the kind of global getting a puppy thing is everybody is just so taken aback by that. I mean, I feel like the fact that puppies use their mouths so voraciously is common knowledge, but, I mean, I guess it’s just one of those things that like, people are like, ”Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah. I know. I heard that.” And then they get in it and they’re like, ”Oh my God, I had no idea it was this much,” you know? There’s just a lack of perspective or realistic expectations. And that’s, I think, been one of my, I’ve discovered is one of my missions or one of the things I really wanna direct my work towards is just getting educating people that like, this is a thing you need to be ready for. Good trainers will help you with the tools to deal with that, but understand this is what you’re getting into. And I think many people don’t, you know. They get a puppy and they’re like, ”Oh my God. t is so cute.” And then the realities of raising a puppy are just, it’s a hard pill for a lot of people to swallow.

Will: Yeah, absolutely. I think, I mean, even if you go into it knowing or thinking, okay, I’m in for something here, there’s still a lot of stuff you’re not ready for.

Ian: Right. Right.

Will: Yeah. What are main the reasons that puppies do are biting or chewing when they’re young? Because I know that there’s, I mean, there’s obviously natural and good things, reasons that they should be chewing and then there’s the bad stuff as well.

Ian: Right. So I think one thing is it’s important, or at least I really try to make a distinction between biting and chewing. And that’s a really common conversation that I have with new puppy owners and dog owners is that those two things are very often kind of conflated together, biting and chewing, but they’re technically separate behaviors that serve different needs for the dog in question. So take chewing for example. So chewing is a passive behavior. It’s a downtempo kind of downshifted, soothing, emotionally gratifying things. So that’s when the dog grabs a toy or, you know, a stuffed animal or something like that and they settle down with it and they start chewing on it. This is very often why you see dogs that go or puppies that go after the chords or the wood or the drywall or something like that because it’s the tactile sensation is interesting to them and they get to engage in that soothing behavior. Now, biting is at different things. So puppy biting is active, it’s up here, it is full on interactivity, right? Chewing is a solitary behavior. Biting is a fully interactive behavior. But part of that is exploratory. So puppies bite in order to receive feedback about the world, and that’s one of the ways that they learn how to function in the world, right? So the biggest thing, reason they do that in the early stages is they’re simulating all sorts of behaviors that may or may not be appropriate when they’re older. In order to get feedback, they bite so that they can get feedback on the force that they’re applying during their bite and then they learn to install kind of some of that subconscious limiting on those things. Like, okay, so I have to watch my force when I use my mouth. I have to watch how often I use my mouth to solve problems or get what I want. I have to be careful about lunging and going after faces and things like that. You know, they do that thing so that they can get feedback on it and hopefully learn.

And so, you know, between those two behaviors, the biting and the chewing, you deal with those with different methodologies. You know, now with puppy chewing, there’s definitely a stage they go through where the chewing kind of gets kicked into overdrive because they’re teething and the chewing soothes the teething. But in my mind for whatever my money’s worth, a well-trained dog continues chewing clear it for the rest of their life because that’s just a good recreational activity for a dog to do that keeps them out of trouble, you know. So I think it’s important to kind of keep those separate and understand that there’s different strategies and methodologies for dealing with those things.

Will: So I guess from that definition, which makes a lot of sense in my mind now, the chewing perspective, you’re trying to channel their chewing into things they’re allowed to chew, so bones, you know, chew toys, that kind of stuff, and away from furniture and etc.

Ian: Correct.

Will: With the biting though, is there a level of biting which is okay, or are you trying to eliminate that out of their behavior completely, and how do you do that?

Ian: Well, you have to do eventually, yes, you wanna eliminate that completely out. But in the interim, you have to work on the progression in the right order. And so the correct order is force first, frequency second, and many, very often folks work on the frequency. They focus completely on the frequency part of it. The problem with that is that force has a timer on it. So usually between 18 weeks and 6 months, the brain chemistry starts to change, and whatever force they’re using with their mouth becomes kind of hardwired in. Like, once a dog goes through adolescence into adulthood, there are currently no behavioral methods to alter the force of a bite. So if you’re working on frequency, which does not have a timer, you can work on frequency at any point in the dog’s life because that’s a manners and obedience problem. So if you focus on frequency only, you never get force training. And those are dogs that are potentially dangerous later in life. So the two variables in a dog’s brain are force is usually measured by what we call acquired bite inhibition, frequency is generally measured by threshold. Like, what is the amount of stress a dog has to undergo before they use their mouth to solve the problem? Well, like I said earlier, puppies do a bunch of knucklehead things because they’re simulating stuff. So they bite even though they’re not necessarily under stress. This is how they simulate those situations and then they get feedback on it, so later in life, when they’re in stressful situations and they feel like using their mouth, there’s that unconscious limiting this. So it’s like, eh, pump the brakes a little bit on that mouth. And that’s an important skill for a dog to have as they navigate through human society, right?

So we do that with pain feedback is the main reason that we…the main method that we use for doing that. Pain feedback and limiting their interactivity, and here’s what I mean by that, right? So puppy’s playing with us, interacting with us, we’re like, “Oh, a little puppy, little puppy, little puppy,” starts chomping, they’re sharky, right? So if I jerk away, I’m triggering that chase drive. I’m just ramping them up. I don’t wanna do that. So I start doing it the same way and adult dog wood, right? So if that dog is hanging off that, puppy’s hanging off an adult dog’s face, at some point that adult dog is like, [barks] And the puppy is like, “Whoa, Whoa, sorry, sorry.” And then the puppy comes in a little softer and the adult’s like, “Okay, we’re back on track. Thanks. No harm, no foul.” And that’s really important, dogs don’t hold a grudge. So the puppy’s doing that, we give them a pain response. We’re like, “Ouch, Hey, don’t do that.” If the puppy bucks their head back, we go, “Hey, great, good job. You and I can continue to interact.” If the puppy comes in again, you know, we give another like, “Ouch, you little worm. Stop it.” If they bought their head back, like fantastic, we’ll continue. If they do not, then here’s the important part. You eject, you completely dip out, interactivity stops. And so it’s very important, and we talk about this a lot with puppies in general, you know, that they have a limited environment. So that means when you’re interacting with the puppy, you’re either in a space that you can escape from or the puppy is tethered to the furniture so that you can escape out of range. It doesn’t work if you take the puppy and put them somewhere because that’s not how they learn. It’s not fast enough.

You need the puppy to understand your behavior has a direct effect on the outcomes that you’re experiencing, right? That doesn’t work the first time, it doesn’t work the second time, it doesn’t even work the 10th time. But by the 25th or 30th time, when I say ouch, the puppy’s like, “That means you are about to leave. I need to start reeling it back,” because they don’t want you to leave. You can dip out if they get too intense, 60 to 90 seconds, you’ll come back. Like, can we try it again? You know, and it’s just, I think where people really struggle with that is, you know, they do that, they hear this advice, then they say, “Well, I said ouch and it jazzed him up.” Okay, well, it’s new to him. You need to do it more, eject. Or like, “Well, I did this for a couple of days and he’s still doing it.” And I’m like, “Do it more.” Like, it takes weeks and sometimes months to get through this, but you have to teach them so that later in life, they have that unconscious limiting, right? So here’s a scenario. Say a dog’s asleep in their living room, you got a three-year-old dog’s asleep in the living room. Toddler runs through, as toddlers do, steps on the dog. Now, a dog that gets startled out of sleep is going to come out, swinging. A dog with great bite inhibition won’t even make contact because he’s got that great unconscious limiting. A dog with very poor bite inhibition might otherwise be a great dog in other aspects but because he doesn’t have that limiter might potentially really hurt that kid, right, because he startled. And so it’s very important I think in my mind to really just work through the problem is unpleasant as it is, wear gardening gloves, if you have to for crying out loud, but work through the problem because the payout later in life, you’re dropping pennies in a savings account that’s gonna pay out tremendously later in life. And so it’s important to do that work.

Will: I like that you mentioned the toddler thing because I think that’s, you know, one of the biggest issues with puppy biting, which may develop into aggression or worse things later in the dog’s life, right, is because you need to work on it when they’re young as you’re saying, so that, you know, it doesn’t potentially resolve in a really bad situation like you kind of touched on there.

Ian: Correct. So just on a side note, one thing, you know, when we’re working with like say aggression or reactivity cases, this is how this all kind of plays out in the long term. You know, any time that we’re working with a dog that has some kind of a ”bad behavior” like that, one of the very first questions in the intake is are there bites on record? Okay, yes, there are bites on record. All right, let’s go down through the bites and get detailed descriptions and I wanna know about what the results were. I really wanna hear about the wounds. I want pictures. I want detailed descriptions. We rate those bites on a scale. There’s a couple of different scales that professionals use. The Dunbar scale has six steps to it, that’s doc to human. There’s the Shannon scale, which has seven steps, that’s dog to dog. And then we use that wound pathology to rate the bites on that scale, you know. Is it, did it make contact? Was it a muzzle punch? Were there bruises? Were there red marks? Were there punctures? Were there deep punctures? Was there shaking, you know? Was the victim killed or consumed? And those creep up the scale. See, that’s important because that tells us the level of that dog’s bite inhibition. That’s more important to me than how often the dog bites. You can have a dog that’s got 10 bites on record and they’re all Level Ones. I’m like, “That’s a non issue. That’s not a problem.” We can also have another dog that has two bites on record, and both of those times people went to the hospital. I’m like, “That’s a dangerous dog.” And we can’t change those things.

Will: Yeah. So that’s the force you’re talking about. That’s the force, level of force. Those rating scales is like, that’s what you’re saying is so important to get under control at a very young formative stage because once they get to a certain age, if they’re already at a six or whatever the rating scale is, they can’t kind of revert back.

Ian: Exactly right. Exactly. Yeah. That’s just, that’s not a matter of if, it’s when, you know, and it’s gonna be bad. Yeah. So I think, you know, one of the biggest problems I see, the pushback I get from a lot of folks when we talk about this is, you know, like, ”So are you saying I’m supposed to let the puppy bite me?” And I’m like, ”Well, no, you just don’t freak out. You know, don’t jerk it. Don’t punish the dog because the dog’s not really doing anything bad. The dog is doing something absolutely natural.” This is where you take a baby and you help them learn to coexist with humans, right? So I mean, you know, you don’t have to sit there and take it. If it’s too much, get up and walk away. If you can’t get away, just be calm. Move the dog off you without freaking out and waving your hands and stuff because that just jazzes them up. And that’s why kids struggle so much with bike training, you know. They’re like, ”Well, I understand what you’re saying, but what do I do with my three-year-old, you know? My three year old just excites him and he just goes after my three-old’s-face.” I’m like, ”Then for the time being, I know you want a family pet, but for the time being, maybe you need to limit the amount of time your three-year-old spends with the puppy because the puppy is not at a point where they can play with a child yet.” That’s just, you know, we don’t send 12-year-olds driving out on the freeway because they’re not ready.

Will: They are not ready. Yeah. I think by accident, I think when we were bringing up our French bulldog, I might have accidentally done what you’re talking about because she’s got a, I believe a very low bite threshold. This is all new information to me, but I’m just thinking on the run. In terms of like, just like, I’d call it a nibble that when we’re playing and stuff like that, she only ever gets to like a nibble stage. It never kind of goes beyond that, but like we’ve played like that since she was a puppy, but like we never let it go beyond, you know, just a really kind of light nibble. And that seems to be now how she behaves. So.

Ian: Sure. Well, so one quick, you know, thing, what you said, like, I love that you mentioned that just to understand the critical differences is if she’s nibbly on you while you are playing, that is a non-stressful interactive kind of event. Now, then my question would be, what is her response under stress, you know, when she crosses her bite threshold? That’s why you can have a dog that has wonderful bite inhibition that can still play tug of war with you and get absolutely savage and into the game. That’s fine. But you get both of those worlds because playing tug is like playing rugby. It’s voluntary, it’s fun and it’s intense. But a bit under stress is like a bar fight. Like that’s not an ideal situation.

Will: Yeah. And I guess you never really know until they’re put in that position, how they’re gonna react, right? And I guess that’s one thing that’s always worried me like toddlers or kids. I mean, as much as people think, Oh, we don’t wanna trust the dog in that situation. You can’t trust the toddler either. If they’re left alone, they start poking the dog in the eye and doing all this stuff to really roll it up. I mean, of course they’re going to react poorly and then, you know, it’s a bad situation.

Ian: Right. I mean, puppies are just, I love puppies and I just love that they’re kind of like sight, but all puppies are just some version of an idiot and you just gotta go into it knowing that, you know, lovable idiot. But, you know, they don’t make good decisions as the toddlers do not.

Will: Yeah, that’s true. So, Ian thanks for all that advice about puppy chewing and biting, it’s really opened my eyes to kind of what the psychology of the situation is and what you need to be watching out for. You’ve got a, so your training methodology has six core beliefs, which I believe you use kind of, for most of your training processes, clients and online and everything like that. Can you give me a bit of a brief overview of how that works and how you use that to train dogs?

Ian: Yeah. Yeah. Those are things I really formulated those really early on and I’m really psyched because they’ve held up as I’ve grown as a trainer over the years. So I’m really big into hexagons. You’ll notice all my material has hexagons all over the place. And so I kind of designed six core beliefs to go along with the six sides. And so the six core beliefs are leadership over dominance, techniques over hardware, management over discipline, leverage over strength, cooperation over confrontation and science over tradition. And so I’ve kind of used those as guiding principles in just shaping the way that I approach, you know, training and behavior and things like that. Did you want me to go into like?

Will: No. That’s probably like a, you know, a 10-year program or something like that, so maybe not.

Ian: Well, listen, I’m a training nerd. So to get me started on this stuff, I’m like a freight train, you know, people like, well, I’ve got a question about something and then I answer it. And then I look over, you know, and they’re like a skeleton with cobwebs on them. Like, Oh my God, I’m sorry.

Will: Well, I think it’s more so I think it was a great lift off point for people to go and check out more about what you’re doing to look into those beliefs and check out all your great videos and all that kind of stuff. I can already, I can tell from just chatting with you for the last half an hour or so that science versus tradition is very prominent in the way you think about things. You’re very much about the scientific side of things and understanding what actually is gonna work for people and how it works. So that’s definitely come across in the conversation so I can already see that principle coming through.

Ian: Thank you. Yeah. That’s I think that’s, we’ve learned more in the last 10 to 15 years about dogs and canine behavior than we have, you know, the whole rest of the time that we’ve had dogs. I mean, 15,000, 20,000 years up to now, it’s just like it is with any scientific discipline, you know, it’s an exponential growth and I there’s so many neat, exciting things that we’ve learned about behavior applied behavior with animals in general, not just dogs. I just feel like that the zeitgeist in dog training just hasn’t caught up yet, you know. I mean I not to denigrate any of my fellow colleagues in the industry because we’re all on the same side, but there’s just still so much stuff that’s, you know, 30, 40, sometimes 50 years old methods out there, and it’s just like, we know more now, you know. We know better and we’ve seen it work. We’ve seen it in action. The peer reviewed papers are out there, man. And it’s just it’s hard to get, you know, the cultural piece to catch up with the science piece.

Will: Yeah, it is interesting you say that because in a lot of areas, I’m seeing trends in the dog space where it’s trying to catch up to what humans have done in terms of whether it’s scientific research, but also, you know, in food and all these different areas. Like it’s really, the education piece is becoming a lot more prevalent and people are making decisions for their dogs based on real info, like research and all that kind of stuff rather than just, Oh, you know what I heard from my grandparents or what I learned when I was a kid kind of thing.

Ian: Yeah. Most definitely. Yeah. Most definitely. You’re exactly right. Yep. And that’s exactly what a lot of people say is just like, yeah, you know, that’s how we’ve always done it or that’s what my grandparents did or my dad did it or, you know, yeah. It’s tough to overcome kind of that lack of momentum, I guess.

Will: Well, it’s in built-in us and I guess, unless you facing, you know, prominent issues that you need to overcome, you probably not willing to break those kind of, if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it, I guess. But.

Ian: Yeah. Yeah. Well, I mean, and that’s how it is with, and not just dog training. I mean, does jeez pick a subject on social media and we described it just now. Yeah.

Will: Okay. So where can people find out more about everything that you’re doing and get in touch and check out all your great content?

Ian: Yeah, we’re all over the place. I mean, we’ve got a website, has a lot of awesome free materials. My business is called Simpawtico Dog Training. I’m sure you’re gonna link to all that jazz. You know, we’re on YouTube, Facebook. We do Facebook lives. We’re real active on that weekly, you know, little things, Instagram, Twitter, LinkedIn, Pinterest, Patrion, we’re all over. My face is all over the bloody place, so.

Will: I’ll make sure it’s all over all of what we’re doing as well and share all that with everyone, so. Ian, thanks so much for coming on ”The Dog Show” today. I’ve learnt a huge amount. It’s been a really, really enjoyable conversation, and I know that all of our listeners would have got a huge amount from it as well.

Ian: Thank you. Thank you. I hope so. And I really appreciate you having me on. It’s just been a pleasure talking with you.

Will: You too. Thanks so much.

Ian: Take care.

From Our Store

-

French Bulldog Coffee Table Book – The Book of Frenchies

From: CAD $53.81 Add to cart -

Dachshund Coffee Table Book – The Book of Dachshunds

From: CAD $53.81 Add to cart -

Pug Coffee Table Book – The Book of Pugs

CAD $53.81 Add to cart -

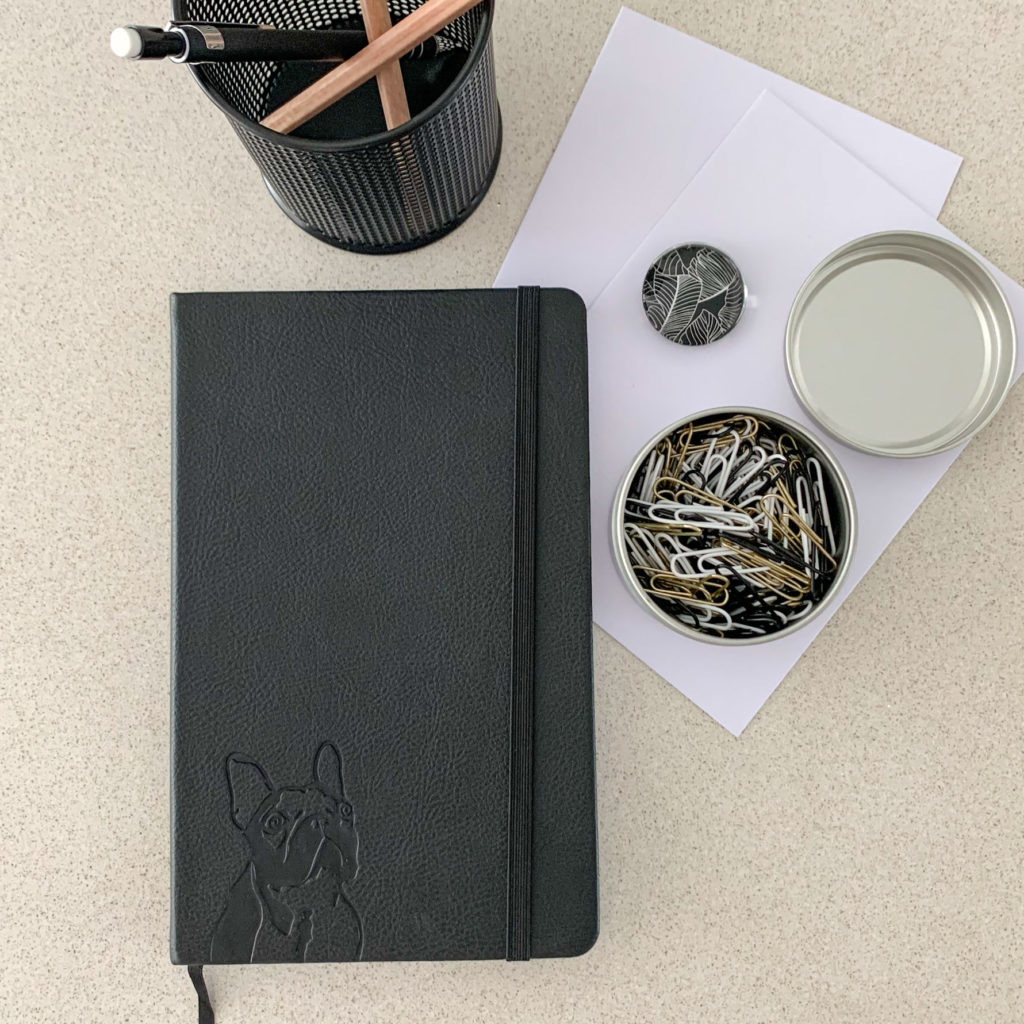

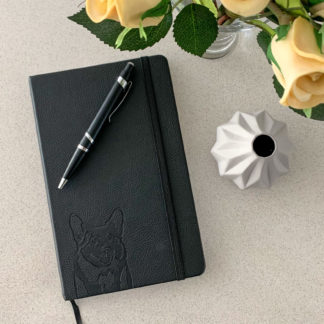

French Bulldog Notebook – A5, Hardcover, PU Leather, 100gsm Lined Pages, Bookmark (Three Colours)

CAD $31.39 Select options -

Dachshund Notebook – A5, Hardcover, PU Leather, 100gsm Lined Pages, Bookmark (Three Colours)

CAD $31.39 Select options -

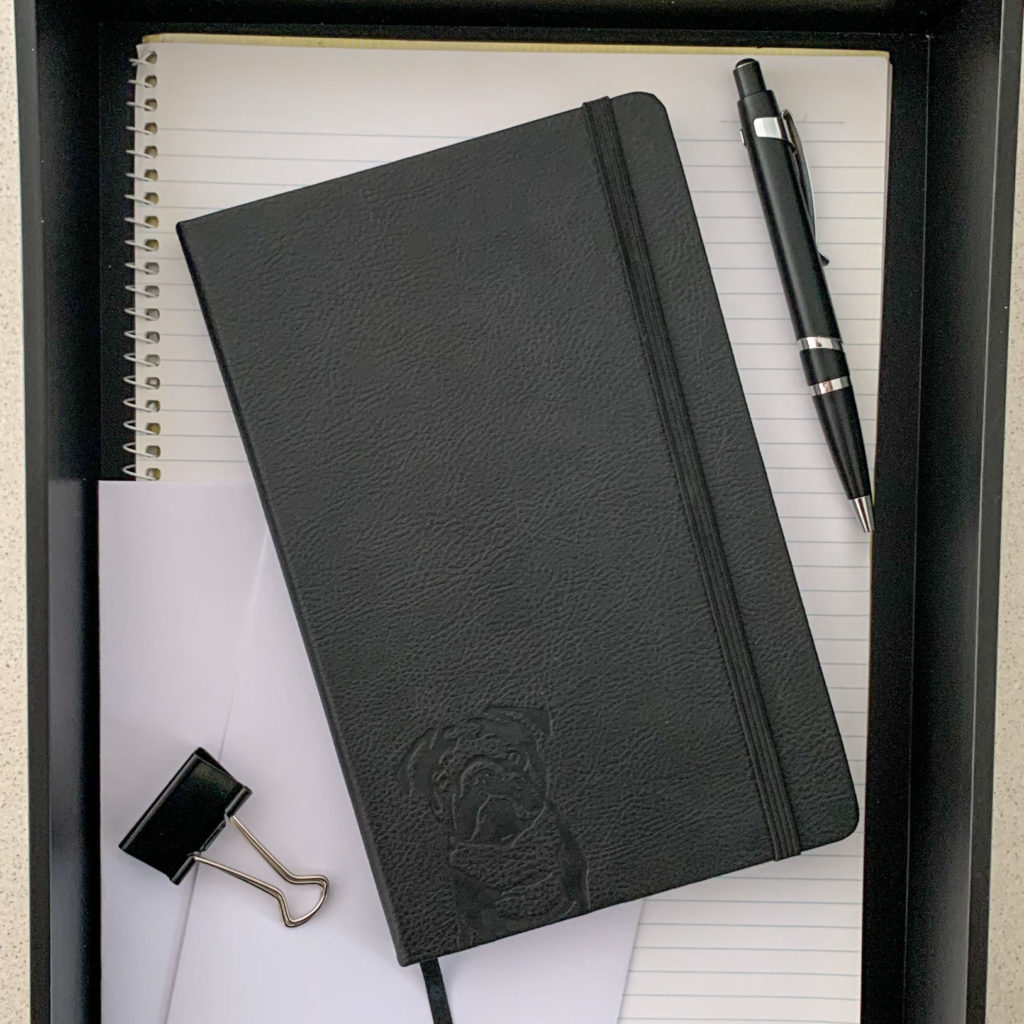

Pug Notebook – A5, Hardcover, Black PU Leather, 100gsm Lined Pages, Bookmark (Three Colours)

CAD $31.39 Select options -

French Bulldog Planner – PU Leather Exterior, Metal Loose Leaf Ring Binder, 100gsm Paper (Two Colours)

CAD $58.30 Select options -

Corgi Notebook – A5, Hardcover, Black PU Leather, 100gsm Lined Pages, Bookmark (Three Colours)

CAD $31.39 Select options -

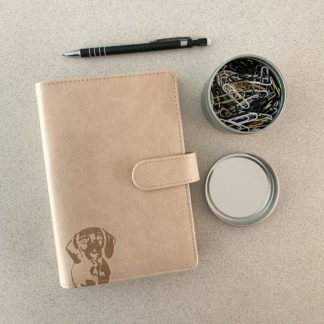

Dachshund Planner – PU Leather Exterior, Metal Loose Leaf Ring Binder, 100gsm Paper (Two Colours)

CAD $58.30 Select options -

Vizsla/Weimaraner Notebook – A5, Hardcover, PU Leather, 100gsm Lined Pages, Bookmark (Three Colours)

CAD $31.39 Select options -

Cavoodle Notebook – A5, Hardcover, Black PU Leather, 100gsm Lined Pages, Bookmark (Three Colours)

CAD $31.39 Select options -

Beagle Notebook – A5, Hardcover, PU Leather, 100gsm Lined Pages, Bookmark (Three Colours)

CAD $31.39 Select options