Want your dog to come when called?

In this episode of The Dog Show, featuring Marc Goldberg, we discuss how to teach a dog to come when called and why it is such an important behavior for your dog to learn.

Marc is co-author of the book The Art of Training Your Dog, a unique guide for gently teaching good behavior using an e-collar.

This book introduces a breakthrough method in dog training. This method taps into a dog’s ancient pack instincts while employing state-of-the-art technology and a game-changing tool: the remote e-collar.

Marc has been training dogs for over 50 years and is a nationally renowned dog trainer. He is also the former president of the International Association of Canine Professionals.

Find out more about Marc and his book here:

Listen

Watch

Read

Will: This episode of “The Dog Show” features Marc Goldberg. Marc is co-author of the book “The Art of Training Your Dog,” a unique guide for gently teaching good behavior using an e-collar. This book introduces a breakthrough method in dog training. This method taps into a dog’s ancient pack instincts while employing state of the art technology and a game-changing tool through a remote e-collar. Marc has been training dogs for over 50 years and is a nationally renowned dog trainer. He’s also the former president of the International Association of Canine Professionals. In the interview, we discussed how to teach your dog to come when called, and why it is such an important behavior for your dog to learn. Marc, welcome back to “The Dog Show.” Thank you so much for coming on the show today.

Marc: Will Blunt, thank you for having me. A pleasure to be with you and your audience today.

Will: Always fun to have a chat. Today we’re going to talk about coming when called. So it’s probably, you know, a challenge that a lot of dog owners are facing especially in the early lives of their dogs when they’re puppies and they’re trying to train them to be that perfect dog that they’re looking for. Why is it important for a dog to come when you call them?

Marc: Actually, I think it’s not only important, I think it’s the single most important thing that you’ll ever teach your dog from the safety standpoint as well as from the psychological standpoint. I mean, think about it for a moment. A dog who comes when called is very unlikely to get hit by a car. A dog who comes when called is very unlikely to bolt out the door because why bolt out the door if you can say, “Hey, get back here,” and I have to do it anyway. You know why eat the laundry? Why get up on the countertops? Why do half of the stuff, you know, that people complain about with their dogs, if you could countermand it with a single word, “Come?”

And what “come” means by the way, guys, is whatever you’re doing, drop it right now, turn around and get back to me instead, right? So it’s just it’s such a giant problem solver. And also too, if you think about it, I mean, most dogs will come when things are boring, they’re hungry, and you’re holding out a treat but you don’t really need that. I mean, that’s nice. That’s a good part of the trick, “Hey, watch this. The dog is bored and hungry and I’ve got food.” But when you really need the dog to come when called is when they’re chasing a squirrel at the wrong end of the field. Okay? So when you ask your dog to come, what you are really preparing for is the day when the perfect storm has come, when that thing that your dog wants above all else is present and it’s a dangerous situation, and you’re going to ask him sacrifice that, do what I’m asking you instead. So it requires a real deep connection to the dog. And I want to start by…

Will: That’s a really good point because…sorry to cut in there. That’s a really good point because I’m just imagining myself with my dog. And, yeah, as you said, if there’s not a lot going on, then they’re quite obedient. But if there is an extreme amount of stimulation, whether it’s kids or other dogs or, you know, exciting things going on down at the park, that’s when it’s the biggest challenge, to get them to respond to you.

Marc: I think that the recall, we dog trainers tend to call it recall, and I think that you don’t really have a recall until you can call your dog off of your worst nightmare, whatever that is, right? So I remember a woman came to see me with a very nice golden retriever, and she had put some training into it and it showed. And one of the things I asked her was how reliable is this recall off leash? And she said, “Oh, no. It’s excellent.” And I said, “So it’s 100%. We don’t need to worry about that at all?” And she said, “Yeah, yeah, there’s one or two things but that’s perfectly in place.” I’m like, “Oh, all right. That’s awesome.” I said, “Let’s go out into the field.” And I have to say this was extremely impressive. But this dog was like running around the field, a big golden retriever and I have, you know, like, an acreage, so there’s plenty to explore, and he was.

And periodically I asked her to call the dog and he did, he would pull his nose off of the grass and come to her. That was really great. Until I asked her to call the dog from about 50 feet away and as he was making his way to her, I pulled out a squeaky toy, squeaked it a bunch of times and then threw it away from her and he immediately abandoned ship. He’s like, “Bye.” And the reason that that’s important is, you know, nobody expects the squirrel or the rabbit or whatever it is. You know, we don’t tend to prepare for it. And then we think, “Well, the dog is pretty good.” But with recall, pretty good is not good enough. You know, eventually, eventually your dog is going to be in a situation where he’s got to make a choice, “Do I want you or do I want that thing?” whatever it is, and naturally, you’re going to be a lot safer if you have prepared for this.

Now, preparation for recall starts early, early on in the relationship. And it starts here. Let’s say we have a puppy or a new rescue dog. So we turn the puppy loose in the room where we want to keep her. And the first thing she does is she wants to explore the room, which is very normal, but she then gets herself into some kind of trouble. She’s heading for the computer cords, or the bookshelf, or laundry or, you know, just something that you don’t want. And so what we typically do is we say, “Hey.” You know, hey is a good American word. “Oi,” in England is what they say.

And then, you know, a nice puppy will stop and look and see what the fuss is about. And if you clap or get low and, you know, indicate that you want the puppy, you know, an 8-week old, 10-week old puppy is gonna come running right toward you. “Yay, Mommy or Daddy wants me,” and they’re happy and excited to do it, right? But as they age a little bit, they start to develop more of that like slightly independent streak, which is a normal part of the growth process, right? In humans, we call it the teenage years, and dogs hit that in a matter of months rather than years. So what happens is we begin to intensify our language as the dog begins to dawdle on that thing he had been doing nicely originally called recall.

And so we might have to say, “Hey, hey,” you know, we just like up the ante. We say it louder. And then usually, that will serve as an interrupter. And then we can redirect the dog back to whatever we want. But there comes a point, Will, where the dog goes, “You know, I’m gonna get back to you on that. I’m very busy. Talk to the paw.” And that’s the point where they just keep their nose, and they’re tearing up or eating, or they’re going to eat that lampshade cord. And so the very next thing that we do is very normal and natural thing is we go grab the puppy. You see these hands, you know, to a puppy they’re like the size of garbage can lids, okay?

So I want all of your listeners to imagine for a moment that they’ve been adopted by some gigantic robotic creature, who just periodically comes at them with a good pair of garbage can lids, you know, picks them up. Well, what starts to happen is puppies and newer rescue dogs, they hear you and they know whatever you’re about to do as the owner is going to be…it’s going to either be mildly unpleasant for me or at the very least, you’re going to be a party pooper. The whole reason that I’m into this laundry or whatever it is that I’m doing is because it’s fun and you’re about to come grab me and stop me. So puppies who have a natural inclination to come if you just feed the beast correctly, and I’m going to describe that momentarily, but what we do is we teach them not only to not come but we teach them to run away because the next thing they start doing is ducking away, shying away. But, you know, they’re young and silly and innocent. So we’re able to quickly scoop them up, “And I told you to, you know, come,” and off we go.

But dogs are a very, very quick study. I mean, they’re based on wolves and wolves are complex problem-solving predators. And this is what the dog is on a domesticated level. They’re very clever creatures. So you don’t have to come at a puppy too many times before they realize, “I got four legs. Let me do some math here. You’ve got two. You’ve only got two.” And before you know it the puppy is scampering away. And usually we’re a little faster and they’re not good at it so we scoop them up. But let me tell you what, guys, three weeks or four weeks after your puppy first starts that, he will have his legs under him, he’ll know how to use them, and then you won’t catch them, and then you won’t catch them. So here’s a couple of tricks. First, what dog trainers don’t do is we don’t yell at and grab our puppies. We also don’t raise free range puppies or free range chickens. Okay? What we like to do is we like to just put a leash on to the collar of the puppy. And I like a good 10, 15-foot leash for this. If there’s a loop on the end, I slice that off because I don’t want it to catch on anything.

Quick word to the wise, never leave a puppy unattended wearing anything like that because you don’t want them to get tangled in anything and hurt themselves. Okay? But if a puppy is dragging a whole bunch of line behind it, and he starts to get into something you don’t want, all you do is you step on the line, you lower your body really low, [vocalization], you call the puppy and you hold out the treat that…you hold out…you hold out the treat that… This, by the way, this is Murphy. Say hi to the people, Murphy. And you hold out the treat and you just bring the puppy towards you, to you and towards you, and then you release the treat. Now ultimately, you know, if you start then raising the treat up, I don’t want you holding treat way in the air or Murphy will jump to get it. But if you take the treat and just raise it a little and move it back towards the eyes, you know, what you’ll find is the puppy will start sitting to get the treat. And that’s when you want to release it.

So we can begin to pattern the puppy to stop what you’re doing when called, to turn around and come to my outstretched hand, which is holding a treat, it’s why I keep them in my pocket. A couple of things, there’s gonna come a point when your puppy says, “You keep that treat. I’m busy out here.” And they don’t come. You’ve stopped them from running away, which is critical but, you know, I don’t want you chasing your puppy either. That teaches defiance. But what I do at that point is if the puppy goes, “I’m not coming,” I do like this, I reel him in just like they were a fist. And I mean, I’m not doing it hard but I bring that puppy in. And then when he is there, I don’t yell at him. I don’t want to disapprove of anything. But I take that treat that I was gonna give them and I stick it right to his nose, right to his mouth, and he’s gonna want it. But I just let him lick it a couple of times and then I take it away. All together, I take it away. I turn him loose. I count to about 10. And then I call him again. And he’s gonna come because he’s gonna be thinking, “I could have had that. You know, I missed my chance.”

And so, listen. With a recall, it starts in babyhood or early in the relationship with a rescue or adult dog. But it starts like this. If you see something you don’t like and you want the dog coming to you, we start by interrupting the behavior that we don’t like. And then we redirect it to something we do, such as the recall. And then we reward for that behavior that we just got. So we interrupt by stopping them with the line, we redirect by asking them to come in, and then we reward once they’ve gotten there, right? Now, if the puppy knows the recall, then… You’ve got to look for opportunities when the puppy doesn’t want to do the recall, to throw it in and make it more meaningful. But this is a good way to start. You start by avoiding… Don’t teach your puppy to flee. Don’t chase them. That would be the first way to start.

Will: So you’re talking predominantly about using a longer lead in that example. In your book, “The Art of Training Your Dog,” you talk about using e-collars. Could you use an e-collar in this situation as well?

Marc: Well, yes, you certainly could. But there’s a couple of buts. There’s a couple of things to know. So, first, we don’t use e-collars on puppies that are younger than 20 weeks, right? So if you’ve got like a 10-week old puppy, the thing is they’re little sponges for information, baby dogs. On the other hand, they have very short attention span. And so we want to work just in tiny, little snippets. And that’s why when we’re raising our own puppies, we have them running around, scampering around on a drag line. And if the puppy happens to look at me and give me eye contact, like, “Hey, Dad, what you’re doing,” that’s what I want to call the puppy. If he’s getting into something naughty that he shouldn’t, I’ll stop and call him and bring him in. But I always want the puppy to say, “Escape is futile but recalls are extremely rewarding.” So that’s where I get really effusive with praise and treats more than anything else.

Okay, now, e-collars, yes, e-collars can be really, really useful in teaching recall because they allow us to touch the dog. And if we’re doing it according to “The Art of Training Your Dogs” method, we can touch the dog from a distance and we can do it very, very gently. It’s just a way of saying, “Excuse me, remember the sequence for recall?” And actually a lot of naughty behavior is we interrupt what we don’t like, and when we’re using the drag line, when we’re using the line to interrupt the behavior. If we’re using an e-collar, we’re using the e-collar in such a way as to teach the dog, when you feel that, “Excuse me, you should look at me, and I’m going to give you information on what I need you to do next, and I’m going to make it fun, and I’m going to make it easy to interpret if you’re a dog,” because there’ll be very clear body language that explains what this silly word “come” means.

And we don’t start there with an e-collar but we get there pretty quickly. We have a 16-lesson plan. It takes six weeks to complete the plan in “The Art of Training Your Dog” and less than seven is recall. We start recall. Ultimately, the average person who trains their dog with, “The Art of Training Your Dog” is gonna have a solid recall within six weeks. And that’s so important because there are people who never ever let their dog off the leash because they don’t trust them. And I think that’s a bit of a sad life that dogs are meant to run and they feel happier when they can.

Will: Does the e-collar become a more of an important tool if it’s, as you mentioned, a rescue or an older dog, an adult dog, which you haven’t had the opportunity to take during the formative years?

Marc: So here’s the thing, let me rephrase that into this question and tell me if this works for you. Let me ask, do you have to train your dog on an e-collar? Can you train a dog without an e-collar? Must you use an e-collar? Should you use an e-collar?” And the answer is…. Listen, I’ve trained dogs for a hundred years, that seems like, before I used e-collars because back in the day e-collars were not gentle. They were not good. The technology was just not there to do this in a nice, reliable way. But today we have e-collars that dogs enjoy the process so much that my dogs, when they see their e-collars, they get happy because they know they’re going to go do stuff. So then the question becomes why use an e-collar? And the answer is anything that I can teach without an e-collar I can teach quicker, much quicker with an e-collar.

So, back to your question. When I was training dogs without e-collars, could I teach a reliable recall to a dog without an e-collar? The answer is absolutely. Did it many, many times. The way we did it was with leashes, longer and longer and lighter and lighter leashes so that when the dog eventually ignored temptation, we could just hold on and, you know, you hit the end of the line, do a little bit backflip and then we could call him again. But the problem was, is it wasn’t always a very nice way of training, you know, because eventually the dog would have to have a rude comeuppance, which is not really part of our e-collar methodology in “The Art of Training Your Dog.”

And secondly, it required an incredible amount of diligence and practice. So to teach off-leash recall to the average dog using old school training, it works. People have been doing it for thousands of years. But I found in my practice, it took about 25 weeks of training and proofing to really get a dog recalling off of a rabbit or a deer. And when I say 25 weeks, I mean that’s practicing a half an hour in the morning, a half an hour in the afternoon, at least 5 days a week for 25 weeks. And then if you’re a talented trainer, you probably have it. But the problem of course is, is that professional trainers never kept dogs for 25 weeks, you know, unless they were maybe hunting dogs, but like pet dogs never…pet dogs would stay for like four or five weeks, six weeks max. So you sort of kind of halfway got them there and then you sent them home.

So the average dog owner, you know, if they got a reliable recall off of everything off of their own dog, it was only because they had a really easy dog, you know, or maybe they were really diligent owners who just put in those many, many weeks of training. Today we’re getting that same level of results not in 25 weeks but in 6 weeks with the book and the methodology in the book, and most importantly of all, I think gently for owners who love their dogs and want to have a good, happy experience.

Will: It’s funny, I’m having a little laugh inside. I’m not sure if you’ve noticed a shift in my questioning. When we first had a conversation a little while ago in episode 27, we spoke all about e-collars. And I know going into that conversation I was coming from a pessimistic point of view. I was thinking, “Oh, e-collars, they’re hurting the dog,” all that kind of stuff. And after that conversation I came in to ask the question today actually thinking e-collars are a positive thing. As you mentioned, it’s more of a nudge. It’s just disrupting the behavior. It’s not hurting the dog based on, you know, how the technology is today. So it didn’t take much for you to keep up to me.

Marc: Yeah. Well, you know, here’s the key point I want to mention. The e-collar is not magic. It’s not like Harry Potter’s magic wand. It’s a communication tool. Now how you use it will determine whether your dog learns quickly, happily, and reliably or not, how you use it. So one of the main problems I think with e-collars is they come without instructions. I mean, you get a little booklet but there’s not a lot of information. And on the internet, there’s a ton of information but a lot of it is conflicting. Just like when we talked about food aggression in a different segment. There’s a lot of information out there. I always tell people who say, “But I read it on the internet.” You know, when I hear silly things regarding dog training, I always want to direct them to the websites which have thousands of members proving that the earth is flat. You know, everything is on the internet. It doesn’t mean it…

So, in the book, we present a really coherent A, B, C, D method so that to the dog, the e-collar becomes merely a tap on the shoulder, which says, “I, as your owner, I want to tell you something, and I want to tell you something important, and I want to tell you right now. And by the way, it’s going to have a good outcome.” So, it may just be, “Hey, we’re turning around at the mailbox. Excuse me, we’re turning around now.” Just the way a friend of yours might tap you on the shoulder and say, “Let’s go down this way instead.” And what the dog learns through this very careful sequence of lessons is that a very low level tap on your shoulder or in the case of the dog, on the neck, means, “Hey, we’re about to do something that you might find interesting. Why don’t you look at me and see what it is.” And at the end of the day, it makes for really happy dogs.

And just to put a fine point on it, I’m talking about levels of this e-collar where I want my owner to hold the collar and feel it, what their dog is feeling, because they’re going to be very surprised. They’re gonna say, “Do it again. That can’t work. I barely feel it myself. Do it again.” But the dogs learn off of a combination of reward, interruption, body language, and honestly, because they love us. And if we will only be coherent trainers that explain to them, “Here’s your choices. Do it your way. Now let’s try it my way. Isn’t this better? Isn’t this more rewarding?” Dogs inevitably prefer to be trained, especially because here’s what they don’t know, once they have a really solid recall, once they’re polite on the leash, you’re going to take them everywhere. You know, “Hey, dog, jump in the car. We’re gonna go do something,” or, “We’re having a barbecue. So come on out and meet the guests and just stay off the table.” But a trained dog gets to be with you and this is what dogs want more than anything.

Will: That’s true, they get to have more fun and they get to be with you more often if they’re well trained. One thing that you said there, which kind of was a lightbulb moment for me, the whole, you know, searching for information on the internet. There’s a lot of people out there and I’ve fallen into this trap before, you’re searching for one specific problem and, “Oh, I need a fix for that and I want a fix for that immediately.” One thing that, you know, for example, your book does at a low price is it gives a system. So it’s not a spot fix for one particular problem but it gives you a system for understanding and training your dog over a six-week period, which can have lasting effects in their life.

Marc: Well, it’s true. So the book does teach, you know, leash manners, come when called, sit at the door, leave it, stay off the kitchen counters, go to your dog bed and wait for me. It does teach all of those things. But I think one of my favorite parts of the book is the appendix. In the appendix, which is called “Dog Behavior Problems,” we list 45 or 50 problems such as, you know, dogs digging holes in the yard, or jumps on guests, or is food aggressive, or is overprotective, or barks excessively, licks items in the dishwasher, I mean, almost anything that a client has complained to us that we got to help. “Please help.” Because here’s the funny thing, Will, very few people come to a dog trainer and say, “Hey, I just want to have a fun time with my dog.” Most people come with a list of the naughtiness, the naughty [inaudible 00:23:30] right? “Just make it stop.”

So we do include 45 or 50 problems in the back of the book. But the reason we put the problems and solutions in the way back of the book is it’s a universal phenomenon if you train your dog to do just like the basic good dog stuff, chances are all the naughty dog stuff will reduce in intensity and frequency. It might even disappear altogether. And the reason for that is the majority of bad dog behavior, digging in the yard, eating the couch, you know, knocking over the kids and playing too rough, all these things, these are either overexcitement issues because the dog is never challenged to focus his thoughts to see what you need or want, so they get overstimulated, or an awful lot of dogs just get bored because we don’t do enough with them.

Or we’ve explained things to the dog in a way that makes sense to us but they’re like, “Lady, dude, I don’t know what you’re trying to tell me here. And you’re trying to tell me so often and so loudly that I think maybe I’ll just, la-la-la-la-la-la-la, you know, ignore you. You’re very nice, but like you’re really incomprehensible.” So, training your dog solves so much of this. Personal boredom and frustration melts away because you’re spending quality time with your dog. You know, this is what they want. And overstimulation melts away because we give you clarity on how to communicate with your dog. So, yeah, what I’ll tell you is the basic training of a dog eliminates 75% of the behavior problems that people complain about. And it’s always a pleasure to send a dog home who did a million wrong things for the family but just I can’t…by the time I send them home two or three weeks later, I almost can’t remember, “What were you in for anyway? I don’t even remember what you did wrong,” because they’re so good.

Will: Yeah. Well, we’ve gone a little bit off topic but there’s awesome…there’s an amazing information there. I think everyone really should check out, “The Art of Training Your Dog,” and “Let Dogs Be Dogs,” which is another one of your books. But today, we’ve spoken about coming when called. You think that’s one of the greatest tools a dog owner can have in their arsenal. So thank you so much for sharing those tips today, Marc.

Marc: Yeah. Thank you, Will. Appreciate you for having me on. And thank you all, to all the listeners for sitting through us or me.

Will: It was fun. It was a lot of fun.

Marc: Thanks, Will.

From Our Store

-

French Bulldog Coffee Table Book – The Book of Frenchies

From: EUR €33.53 Add to cart -

Dachshund Coffee Table Book – The Book of Dachshunds

From: EUR €33.53 Add to cart -

Pug Coffee Table Book – The Book of Pugs

EUR €33.53 Add to cart -

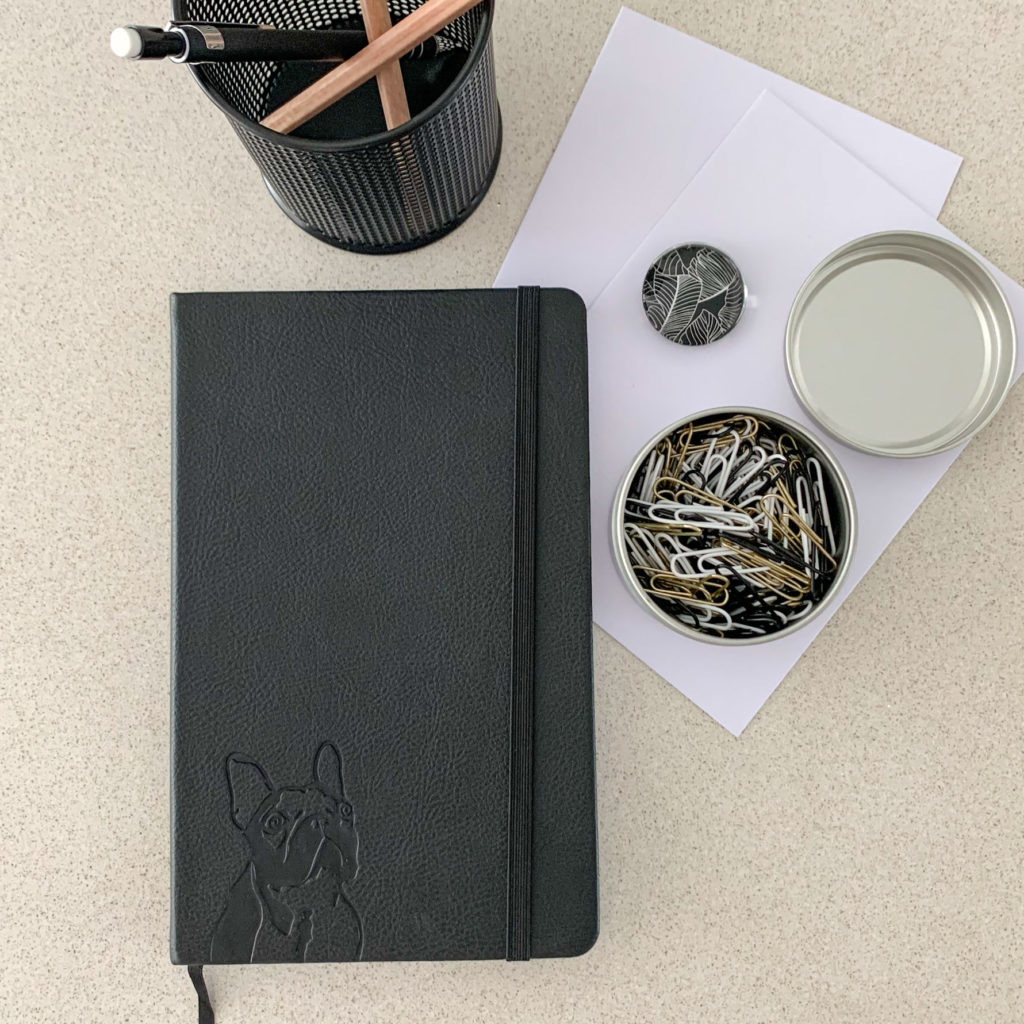

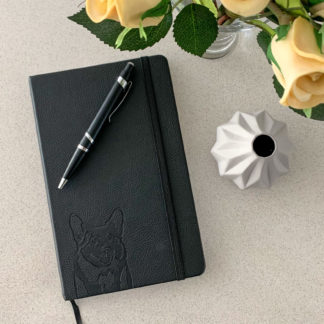

French Bulldog Notebook – A5, Hardcover, PU Leather, 100gsm Lined Pages, Bookmark (Three Colours)

EUR €19.56 Select options -

Dachshund Notebook – A5, Hardcover, PU Leather, 100gsm Lined Pages, Bookmark (Three Colours)

EUR €19.56 Select options -

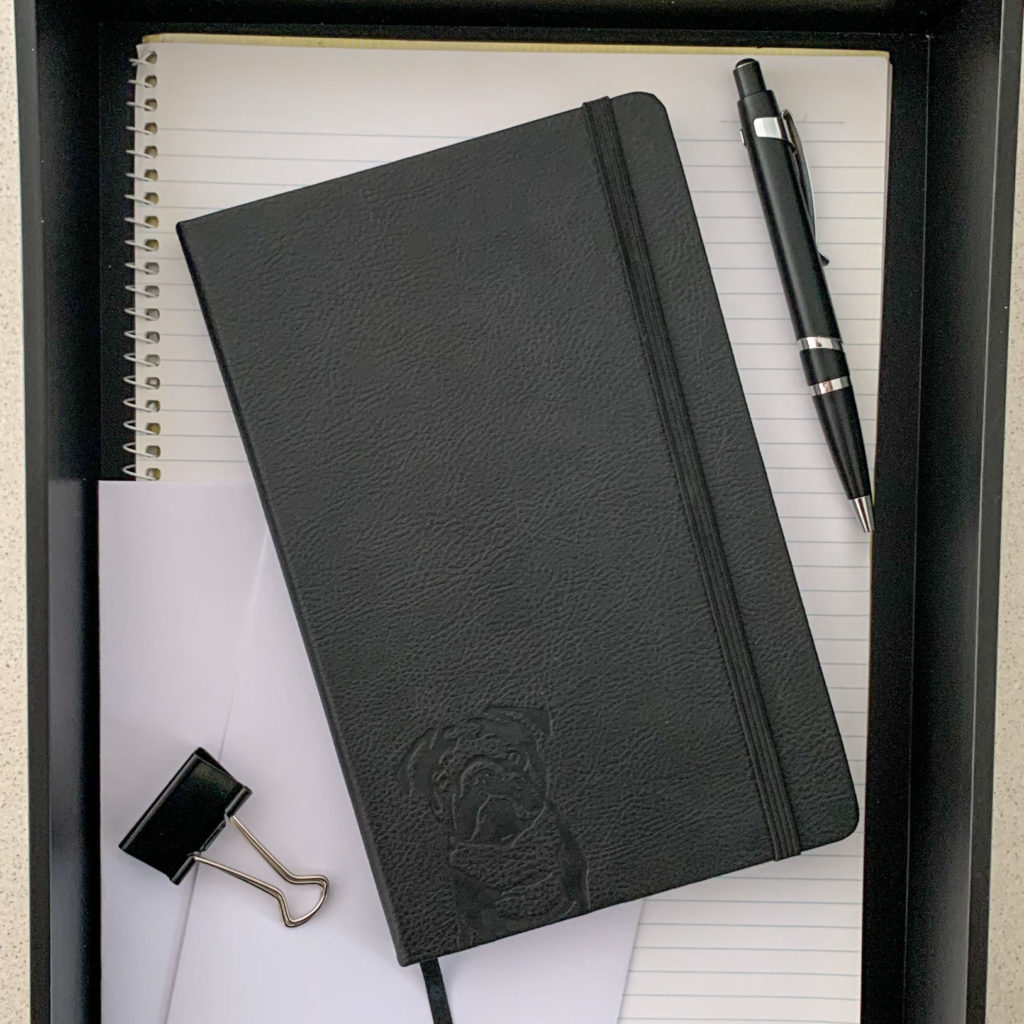

Pug Notebook – A5, Hardcover, Black PU Leather, 100gsm Lined Pages, Bookmark (Three Colours)

EUR €19.56 Select options -

French Bulldog Planner – PU Leather Exterior, Metal Loose Leaf Ring Binder, 100gsm Paper (Two Colours)

EUR €36.33 Select options -

Corgi Notebook – A5, Hardcover, Black PU Leather, 100gsm Lined Pages, Bookmark (Three Colours)

EUR €19.56 Select options -

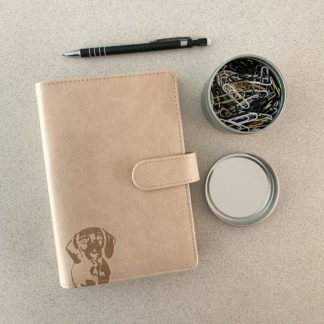

Dachshund Planner – PU Leather Exterior, Metal Loose Leaf Ring Binder, 100gsm Paper (Two Colours)

EUR €36.33 Select options -

Vizsla/Weimaraner Notebook – A5, Hardcover, PU Leather, 100gsm Lined Pages, Bookmark (Three Colours)

EUR €19.56 Select options -

Cavoodle Notebook – A5, Hardcover, Black PU Leather, 100gsm Lined Pages, Bookmark (Three Colours)

EUR €19.56 Select options -

Beagle Notebook – A5, Hardcover, PU Leather, 100gsm Lined Pages, Bookmark (Three Colours)

EUR €19.56 Select options